Interviews

Interview with Klayton – Circle Of Dust – November 21st, 2016

Industrial is a term that was used to describe a great many bands in the 1980s and 1990s. The term became so hated by the very people involved in its inception, it became an easy way to irritate the musician simply by describing them as such. Now, twenty-five years later, Industrial is a badge of honour for bands like Einsturzende Neubauten, J.G. Thirlwell, Skinny Puppy, Front 242, Nitzer Ebb, Ministry, KMFDM, and Nine Inch Nails (to name VERY few of the genres’ greats).

One band that always hit the ball out of the park but never received the accolades the material deserved was Circle Of Dust, boasting four wonderful releases under a variety of monikers (Brainchild, Metamorphosis and Argyle Park) and released on an obscure Nashville record label that went bankrupt and took the band’s music rights into lockdown for almost two decades. The awesome Argyle Park album touted collaborations with Tommy Victor of Prong, J.G. Thirlwell of Foetus and Mark Salomon (Stavesacre/Crucified).

After almost two decades of attempting to secure his original masters from the depths of a legal stranglehold, Circle of Dust mastermind Klayton (Celldweller) finally re-acquired the rights to his original Circle Of Dust catalog. Earlier this year, Klayton remastered and re-released deluxe versions of said catalog, featuring over 11 hours of music across 175 tracks from the following 5 albums: Circle of Dust (self-titled), Brainchild, Metamorphosis, Disengage and Argyle Park. If you have never heard this stuff (and many haven’t) you are in for a real treat. They are all available to stream on Spotify and Apple Music, but the majority of the new unreleased material is wisely held back for purchase only as digital or physical releases (available here: https://fixtstore.com/collections/circle-of-dust)

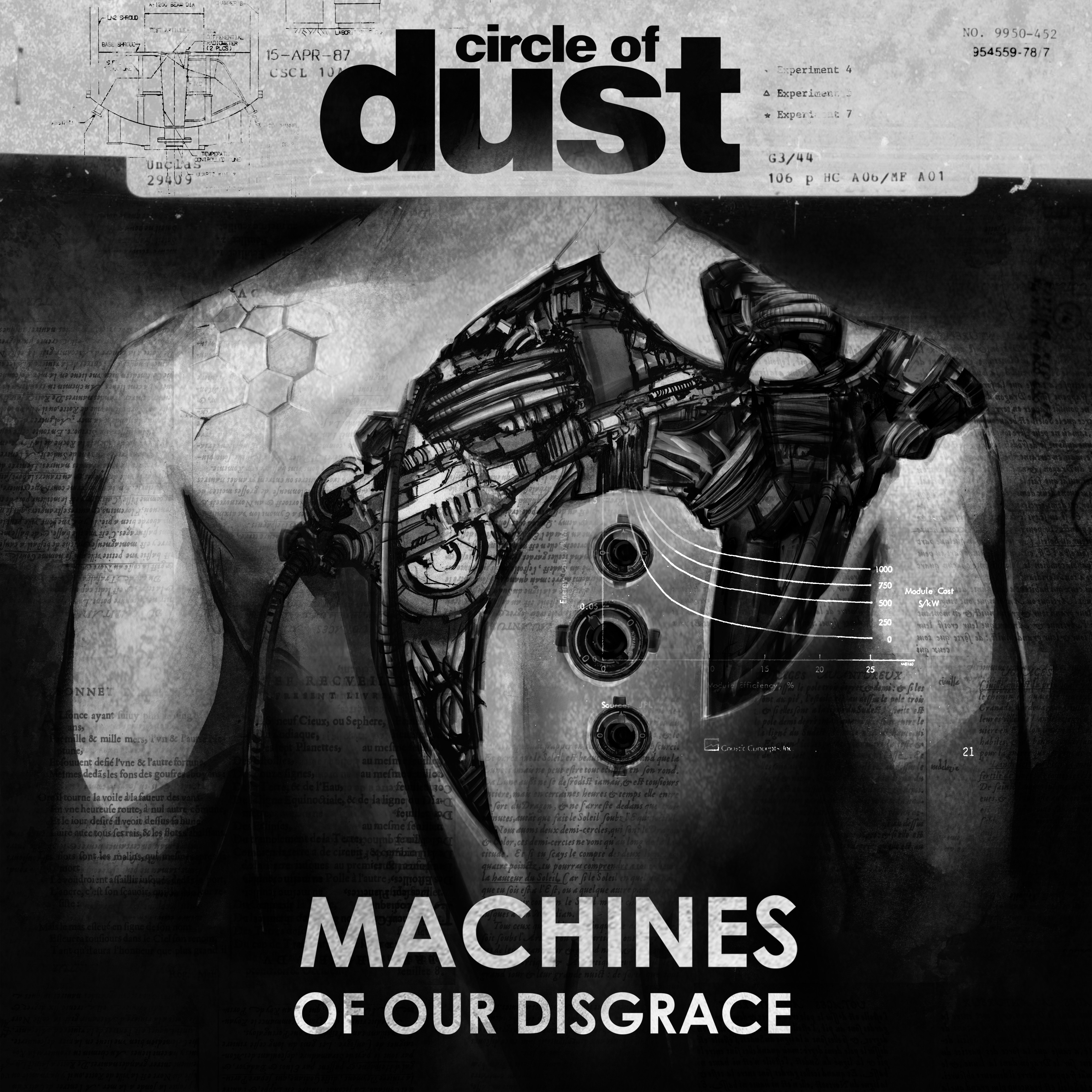

Klayton was good enough to take a half hour of time and discuss Circle Of Dust at length, the legalities that tied the project up for decades, and his return to the project after years of repeatedly saying Circle Of Dust was dead. Machines Of Our Disgrace is a complete breath of fresh air to the genre, not trying to be anything more than a modern extension of a project that was swallowed up by the combined might of lawyers and the ever-shifting music industry eons ago.

I am thrilled that Circle Of Dust is putting out new material. I had lost track of you for the past twenty years, so this is pretty exciting.

Klayton: Well, I’ve lost track of me for the past twenty years too. So we have something in common. (laughs) James said that you were familiar with Circle back when I was originally making that music. So that’s kind of interesting – finding people coming out of the woodwork that remember twenty-year-old albums.”

I still play that old stuff.

“The interest in the new material has been pretty good.”

That’s good to hear. It’s a different climate than 25 years ago.

“Very. That is part of the reason why I felt it was just time to try it again. Really, this was more for me.”

Until getting the PR blast about this new Circle Of Dust album, I thought you’d stopped making music after Disengage came out in the 1990s. I thought you’d maybe started a family or just gotten into another line of work. I didn’t realize that you have been active over the past two decades.

“Yeah, I never stopped. I just kept going from one project to another. A big part of the reason I killed Circle of Dust was because the record label I was signed to went bankrupt. There were basically saying “We can’t give you money for a new album. You can’t make a new album. But you are still under contract with us. So you can’t go anywhere else.”

That’s whacked.

“Yeah. So I had to find other ways to make music and make money. That was when I met Criss Angel. He and I started making music. He actually hired me to produce. I needed to take that gig because I really needed to make money at that time. I just decided that I’d done Circle enough. There were enough stigmas attached to it that I wanted to shed. I wanted to move on and do something different. So I decided to start a new moniker. I was getting into more European style electronic music and drum and bass and Psy Trance and stuff like that. I decided that Celldweller was the thing I was going to pursue. So I never stopped. I never got a day job. I just stopped making Circle and moved on to making Celldweller.”

Knowing that R.E.X. locked you out of your ability to make music and took all of your previously recorded music, was that a hard thing to do – walking away from Circle like that?

“Well, not really. Maybe from the outside in when you see me release albums it could be a disconnect watching me go from one sound to another sound. But really, for me, there was years or space between doing some of that stuff. During that time I was ingesting different kinds of music. I was experimenting with production that was different than what I was doing for Circle Of Dust. So when I finally did it, I was excited to try something new. If it was just a conscious thing – “I think I should just change my sound.” – I don’t even know how I would do that. A lot of what I do artistically and musically is because I am motivated and inspired to do something in that fashion. So that was the transition to Celldweller.”

I’m 49. I’m a Jim Thirlwell fan. And I love Al Jourgensen. And the Wax Trax bands. All of those guys use different acronyms, monikers, and pseudonyms to release material. So it’s not an uncommon thing within the genre to have to chase after music / composers who record material under a variety of names. I would lump your in with that ilk of composers if you will allow it.

“Yeah, I was. If you knew about the Argyle Park album that I did during the Circle of Dust era, I did that in 94, Jim Thirlwell was on it, Tommy Victor from Prong, and the guys from Drown, Warren and Marco. I used three pseudonyms on that album because one wasn’t enough. I made it look like a three piece band. Two of the band members were me and one of them was Buka. I think I just changed my name a lot. And wanted to do projects because I kind of wanted to hide behind my production. I wasn’t really confident in my production at the time so not using my real name helped me be a little more anonymous and I felt a little more free to experiment and not really worry about what anybody said about it.”

That’s curious. Back then, and I’m going back to 1991 and 92, I was a big Skinny Puppy fan and a big Ministry fan – and a pal that I was going to college with tossed me the Brainchild album and I can remember thinking: “This is fucking awesome.” Good soundbites, good clips from movies, production was tight, and boasting the heavy guitaring which I tend to enjoy within that style of music. So that was a no-brainer for me.

“Yeah, I was just so young in production that I just assumed that everything I was doing was wrong. That the albums just sounded bad. My ideas were terrible. That’s just kind of how I spent the first few years of my career – thinking that everything that I was doing was wrong. It took 15 years in doing production for me to realize that even if I’m doing it wrong, it doesn’t matter. People like it and I dig what I’m doing. So it doesn’t matter.”

Can you talk a bit about what you after Circle of Dust? You talked a little bit about Celldweller. And some European electronics. Maybe fill in the blanks in a bit more detail about what you have been doing since Disengage was released? There are twenty years of fillable time there. Were you doing any film work, raising a family?

“No family to speak of. My whole life is music and making music. That is really where I have focused all of my attention. So it wasn’t even from Disengage. Disengage happened in the middle. Probably Argyle Park was the last album that I put out, which was that collaborative project on the same label. The label went belly up and basically said I can’t do anything else. This guy Criss Angel started calling me up while I was out on tour and he was saying that he wanted to record a musical project and that he needed to update his sound. He was really into my albums. It turned out that his cousin worked with my dad, and he wound up getting a cassette of my music that way. We ended up becoming friends, Criss and I. I was finally freed up around this time to m,ake a new album, really to free up the debt for the attorneys that I had to hire to get me out of the R.E.X. record deal. So I got an advance to make disengage and basically just spent all of the money to pay off the debt that I was put into. It was kind of a mess. But I worked with Criss for a few years and decided after a bit that he really wanted to push his whole magic thing. For me, it was always about music. That’s really what I cared about. So I decided to split off and start Celldweller. So in ’99 I officially started writing demos for Celldweller. And I ended up getting a record deal in about 2001. A big record deal with a division of Walden Media. They make films but they started a record label division. I was the first and only artist that they signed. I got a big advance. The biggest I’d ever seen. More than I’d ever seen in my life. I paid myself out of all of the debt that I’d put myself in as well, and then 9/11 happened here in the States and the economy kind of tanked. They basically called one day and said “Hey, we’re not going to do the record label thing. And ps: you need to give us back all of that money.” So I wound up getting out of debt and going straight back into it worse than I was before. My wages were garnished for a number of years. Any money I generated, a pretty significant amount was garnished. I went right back into the whole and trying to survive. So I finished the Celldweller album on my own. I have a friend Grant (Mohrman) who has a studio. I finished it up with him out in Michigan. That was how I wound up in Detroit, I came out to work with him. So I finished the album independently, and it debuted on the Billboard charts. A completely independent album, and a first-time artist as far as most of the world was concerned, and it showed me that there was still that Circle of Dust fanbase following me around. Why else would anybody care about Celldweller? Who would even know about it, right? So I was fortunate to build a fanbase who really have remained faithful for, as you can tell, decades. I just announced that I was re-releasing all of my old Circle Of Dust albums and resurrecting the project for a new album and the response has been surprisingly overwhelming.”

Brainchild was like that cool platter you would pull out for pals whole liked the more renown industrial acts. It was easy to hand it to someone and say “If you are playing this (insert popular industrial album) then you would probably like Brainchild. or Metamorphosis. And anytime I played your music for someone already into the genre, it was like flicking a light switch on for them. Every time.

“(laughs)”

And then they couldn’t find the material, right? Because R.E.X. albums weren’t easy to find back in the day. It was hard to get anything on that label. I had to go to a religious record store that I’d never been into before in the city I lived in to buy your music. it always felt strange to me that that was where I was going to get my hit of industrial music, you know what I mean?

“Yeah. That was part of their whole set up. There wasn’t much I could do. From my side, it was kind of weird as well. Always telling people that you can’t really find this album anywhere. And there really was no web back then. You couldn’t just login to Amazon Prime and get it two days later. It just didn’t work like that. So, I made this music. I dumped my heart and soul into it. I really made no money doing it. I never got a dime from the label outside of a few small advances to buy myself the gear I needed to make the album. for the most part, if they put me up in a studio, they just paid the studio directly. I drove there in my own car with my own gear. Recorded in ten days. I didn’t get any money for food or anything. I was pretty much all on my own dime. And then I went home. They made five albums and until this year, 2016, I’ve never really seen one dime of income from it.”

Wow. Insane.

“Yeah, it kind of is. But you know, there was nothing I could do. Here I was in school to be a doctor. I was studying to be a doctor in college. That’s what I was going to do. and I didn’t like people enough to really BE a doctor, but I was kind of fascinated with the human body and how it worked. So I was going to pursue that. And then through a series of events, I knew some guys who were signed to the label, and one of the guys in the band, they were called Believer, (Kurt Bachman) became the A&R guy for the label (R.E.X.). I gave him a demo of something I’d been working on and he was like, “Hey. We want to sign you.” It happened like that. Unbelievable. So I basically said, “Ok. I’m leaving school because this is what I really want to do. And I knew it would be hard to make money. Because, how do you make money making music? It’s impossible.” But I had to try. I worked a job and that’s how I made my first three albums. The first Circle of Dust, Brainchild and Metamorphosis. I worked a full-time job. Full time and then I made music the rest of the time. That was my whole life. I didn’t really have a social life. (laughs) Nothing. I wanted to make music. So that’s what I really focused on.”

And you know, in my head, without knowing you were going to try for being a doctor, that is pretty much how I always imagined you. Dedicated to your craft.

“Yeah.”

So, you get all the rights to your music back. And you have all of the original stems to your music again. What was the process you used to bring them into the present 2016 era? What did you have to do to those old songs to re-release them?

“Well, I had tried probably 6 or 7 times over the last 15 years to buy back my masters from the people that ‘owned’ them. Because that product was gone. It wasn’t distributed anywhere. It was barely even in the digital format. It wasn’t up anywhere. It wasn’t up on iTunes or Spotify. Maybe one album was. Nobody knew about them. The masters were being sold to a company. And that company would then sell them to somebody else. It took us a while to track them down. And then trying to buy them back for years was generally met with resistance. “We don’t sell masters” being the blanket response. Or, we’d get “Ok. Give us a hundred grand and you can have your masters back.” It was ridiculous, I don’t even know that I saw $100.00 in advances. I bought a sampler at one point, so I must have gotten at least that. But it wasn’t much. I don’t know how those albums could have accrued that much debt. It was a little bit ridiculous. Finally, we went back and pled our case. My manager James really is responsible for making it happen. He really made them understand that those masters weren’t going to make them a single dime. But for a lump sum of money, he would pay them to get the masters back for the artist (me), because they were important to him. he wanted his masters back. And somehow, some way, for the first time in 15 years of trying, somebody finally said yes. I couldn’t believe it. So really, there were no stems. There was nothing more than what I already owned. I had some ADAT tapes that I recorded some of these albums on (note: ADAT is a magnetic tape format used for the recording of eight digital audio tracks onto a Super VHS tape). Some of these albums were just on DAT tape. In fact, some of them were just on CD. The CD itself became the master. I ripped high definition versions off of the CD and then remastered them. Two track masters for the most part. I didn’t go back and remix songs. There was a couple that I did that one. ‘Exploration’ off of my first album, I actually had enough content here that I could actually redo the song from scratch – so I did that for the song. For the most part, a lot of the main albums were just remastered. And they sound considerably better than they did when they were released twenty to twenty-five years ago.”

I haven’t bought them yet. I’m going to buy them off of the FiXT site. But I still have cassettes and a couple of original CDs of the R.E.X. albums. And you can stream what you have done on Apple Music and Spotify – But not the full expanded remastered extra tracks. You have wisely held some of that bonus content back for actual purchase.

“Yeah, yeah. Exactly. That is mainly the stuff that I have remastered. The stuff that you are not getting on streaming is all of the extra bonus content. There’s demos; some unreleased tracks; some acoustic versions of songs like ‘Waste Of Time’ and other tracks that have never been heard before. There’ds a lot of content that I wanted to keep just specific to the fans that really wanted that content. I didn’t want someone who is casually going to listen, wondering what Circle of Dust is, and they hear a bunch of filler, you know?”

That’s smart. You might actually make a dollar off of some of this stuff now, right? people like myself will buy it. I like owning physical copies of music I love. And I am keen to hear this extra content.

“Yeah! The fact that I am able to generate new merchandise and be able to sell these albums again, they are selling like I never stopped making music. it was kind of crazy to me that the enthusiasm is there. The fanbase is pretty small, really, in the grand scheme of things. But they are die-hards. It’s a situation like “where else can you get this music?” So they have been really passionate about getting these albums remastered and getting them back as releases. There’s bonus content and there’s new merchandise now available. And the fact that there is a brand new album coming out, I feel like are a lot of people who are pretty happy about the fact that I got the masters back.”

Absolutely. I have to think that being able to get them back and work on them again in a production to realize all of the filler stuff helped provide the impetus for you to attempt a new Circle Of Dust album.

“Yeah, it did. Really, I’ve been on record many times saying that I have no desire to ever talk about Circle Of Dust again. That it was the past and to just leave it. I was doing something else with Celldweller. But when I finally got those rights back for those albums and I realized “Wow. All of this hard work that I put into these albums and I now can actually do what I want with them. That changed the whole game for me.” I knew I could make those albums sound better. And I could add a bunch of content that no one has ever heard before. And then I thought, “Hey, I’m in 2016 now. I know how to produce a lot better than I did back then. What would new Circle of Dust even be?” And I couldn’t stop thinking about it. And then I started getting excited about trying that. What does that mean now? How do I sample and treat my processes in the way that I did back then but in a much more modern and sophisticated way?And that was my challenge for a new album.”

That must have been kind of surreal. The technology being what it is now is so different than back in the early nineties.

“So different. And part of what I wanted to do was to actually go back use some of the things that I had at my disposal when I made those original albums. I did that. I pulled up old sample banks from these albums. Some drum sounds. I went the distance and took modern sample packs, samples that you can buy commercially for producers. Instead of taking them out of movies and I actually recorded them into that same sampler that I had that I did those early albums on. By today’s standards, a pretty lo-fi sampler, but for that very reason, it gives it a certain quality and a certain sound. And I sampled a bunch of modern sounds into the sampler and then I actually made songs in the sampler the same way I did back in 1990.”

I think those Lo-Fi sounds make the Machines of Our Disgrace sound authentic. Like a natural step from where you left off. And the samples sound like they have been lifted from some old 1950s horror film that doesn’t exist, right?

“Yes. Exactly.”

That’s cool. Some of your early material, there is a tune on Brainchild that is a lift from Rutger Hauer’s speech from Blade Runner. You probably couldn’t do that now, right?

“(laughs) No. Unfortunately, those days are over. So I definitely stay completely clear of unlicensed stuff. I did find some resources where I can get soundbites from movies and stuff that are completely copyright free. Which is great. And that is kind of what I did for this album. It retains the feel of what Circle Of Dust is but being hopefully free of lawsuits and things like that.”

Wow. Knock on some wood there Klayton. It’s like the record industry has treated Circle Of Dust like a baby treats a diaper for the first ten years of your career. (laughs)

“Yeah. Very true.”

What do you think you would be like if you were seventeen years old right now trying to cut into the music industry right now? Do you ever think about that? Easier of harder?

“Yeah, I have thought about that a lot, actually. I give that advice out to fans. I give videos talking about that very same thing. In fact, I did a video interview this morning where I touched on that briefly. I think my career trajectory would be completely different than it was. And I’m not saying that in a good way or a bad way. I don’t really know. I do know that I would have tools at my disposal that would boggle the mind if I knew that I could do that in the nineties. I didn’t have digital audio. I wasn’t recording into a computer. I mean, I didn’t even own a computer. I only had a sampler and that was only because I got a record deal and I told them I need a sampler to make an album – so you need to buy me a sampler. So, having these modern tools, You can get even a beat up, old computer that can run software that can actually end up producing. If you have the know-how, you can produce pretty good sounding music. And you have YouTube. There are teraflops of video tutorials out there if you want them. Anything you want to know how to do, you can just search it on youtube and find somebody who will show you how to do that exact thing. I’m not even talking music now. I’m talking anything.”

Anything. It’s very true.

“You want to know how to change a car battery, it’s on YouTube. So being 17 and saying: “I want to produce.” and being able to just call up tutorials on youtube, I would be so far ahead of the curve compared to the path that I had to take where I pretty much had to learn everything on my own through a lot of trial and error. And a lot of those early albums were more error than they were anything else. I feel like I didn’t really know what I was doing on them. And therefore the albums didn’t really end up sounding that good. Especially compared to what I know now.”

Yeah. But I still think you are doing yourself a disservice. There was a lot of skeef back then and I don’t lump any of your stuff in what that skeef. Your material never sounded like a lot of the mid-level or low-level quote unquote industrial music that was floating around in the late eighties and early nineties.

“Yeah. There was a lot of filler. And that wasn’t what I aspired to be. I generally latched onto a few artists that I thought were great and everything I was doing I was trying to be like them. When I first heard Depeche Mode, even though that wasn’t anything like my industrial influence, their production on Violator, let’s say, the sound they had on their basslines, I was just blown away. I was going for that. I was too dumb to know at the time that I didn’t have the right tools to do that. I wasn’t in a million dollar studio. And I didn’t have a bunch of analog synthesizers with resonant filters. I tried everything that I could do to make sounds. I always tried to write good songs and make good sounding stuff. I ended up creating a better result because I didn’t realize at the time that I really shouldn’t be able to do it. I really didn’t have the tools to pull that off. But I pulled more out of the gear than I should have because I was kind of too dumb to know that I didn’t have the know-how to do that.”

Yeah. And the best film directors, comic book creators and video game developers, they all have the same story, right? They just strived for the best they could get with what they had to work with.

“Yes. You are not looking at it like this is an impossibility and I’m never going to be able to do it. You are looking at it like “I need to do ‘that’. These are the tools that I have to work with. So let’s go. Let’s do this.”

I noticed the pre-orders for your new album Machines of Our Disgrace went live a few days ago in numerous configurations. That has to feel pretty rewarding to you.

“It’s like you said earlier, pretty surreal. It’s strange for me, even to this day looking at an album cover that says Circle Of Dust that I made in 2016. I’ve been on record many times saying I would never talk about this again, and here I am looking at an album that I made quickly, within this calendar year. And it’s going live. It is. Very surreal.”

One thing I didn’t see for your re-issues and the preorder for this new album was vinyl. Do you think that will happen?

“Well, I did vinyl on the last Celldweller album and it didn’t perform as well as everyone thought it would. I kept getting notes saying “Make vinyl. Make vinyl.” So I made vinyl and it didn’t really fly off the shelves.”

Interesting.

“I sold a decent amount. But not flying out the door. I’m actually having more luck with cassettes, which is ridiculous.”

It is. That made me laugh when I saw it on the FiXT site.

“It seems ridiculous. But I just did an eighties new wave project that I have called Scandroid, I just released the debut album about a month ago, and it’s a very different sound than Circle, but it’s somewhat related in that it’s derived from eighties electronic music – but much lighter. I decided because that scene was so big into the medium, I’m going to do a limited run of cassettes. And in the pre-order period before the album was even released, the cassettes were sold out. Clearly, there is a demand for them. So I’m doing fairly low runs of cassettes even for Circle. It’s not like I expect anybody to crack out their Walkman’s and listen to the album. But there is definitely a nostalgia factor. For me, it brought it all back. I used to make music for cassette release. That was really the only medium that there was. CDs were starting to come in. But cassettes were cheaper, so there were a lot of people still buying cassettes back then when I was making those early Circle of Dust albums.”

I generally hate asking this question, but at the same time it’s something I genuinely want to know. So I tend to ask it. What does your writing process look like Klayton? Do you feel your approach to writing is likely the same as other musicians? Or do you feel that you are unique within the style of music that you make?

“I never really compare myself to other musicians. Mostly because I don’t really know what most of them do. I said this today, actually, in another interview, and it’s true. For a large portion of my career, whatever I was doing, I was pretty much sure that I was doing the wrong thing. Whatever I was doing, It wasn’t the way that everybody else was doing it. It couldn’t be, because I didn’t learn from anybody. I made my own mistakes. This is how I can do it, but it can’t be right. I never really did that – think that compared to this guy or that guy, I’m really kicking ass. At the end of the day, people like you don’t really care. You just want to love the music. Or you don’t. I always strived to make a good product in the only way that I knew how. Over time, I started having access to other producers because the web brought us closer together. You can now trade tricks with other people and learn things. So my process is something that I have hashed out on my own, and figured out for myself. It’s kind of always evolving too. I’m always looking for new tricks and new techniques. Some songs come together really quickly and some songs take a really long time. I wish I could say that I have a really quick formula and articulate the way that I do things from A to Z, but it is never really the same from track to track.”

Do you plan on touring Machines of Our Disgrace?

“Probably not. I don’t think that I would tour ever as Circle Of Dust. Or Scandroid. Those are my two side projects, Celldweller being my main project. I feel like I would only ever tour Celldweller. But I have had a thought about a future Celldweller tour where I would incorporate some Circle of Dust and some Scandroid. It’s almost like Celldweller and special guests. All in one show, I suppose.”

What’s your pet peeve when it comes to being reviewed as an artist? Do you have anything that makes you roll your eyes when you read it or see it online?

“The good new is I’ve grown a pretty thick skin when it comes to that stuff. Comparisons always kind of annoy me. I think they annoy a lot of artists. You hate when you try and do something creative and say “This is me.” And then somebody goes “this guy sounds like this, this and this.” Ok, cool. You just took all of the originality out of my music. Thankfully I’ve gotten to a point in my career where there is not many things in my career that you can compare me to. There is not really that much music that really sounds like what I do. And that’s not because I was trying to do that, it just seems to be what has naturally come out. So in the early days, the industrial albums, it was always that. Sounds like Skinny Puppy meets Ministry. Or whatever the comparisons were back then. Back then I was like, “Ok, that’s cool. That’s a compliment.” Those were the elite bands in the scene at the time. Over the years, I’ve just kind of numbed. In the days of YouTube comments, how shocking can you be anymore? How can you be offended? (laughs) Human nature comes out in a really vicious way in comments on social platforms. I just generally tend to ignore a lot of that stuff.”

The way music marketing currently works online, it’s all algorithms and intuitive cookies – essentially doing what you just said: “if you like this track or album, you will probably like this, this and this. The internet: ruining artist’s authenticity one click at a time.

“(laughs) Spotify, Apple Music and Pandora, absolutely, it’s all just based on your habits and listens. Nowadays, there is a point where comparisons are good. It at least gets you lumped into the right circles.”

I’ll finish off with one last one. What’s the one thing you hope people will take away from Machines of Our Disgrace, Klayton? A feeling vibe or consensus you hope they grasp from the new music.

“Probably that they are not alone. If you can feel at all like you can relate to anything I’m saying in the lyrics, then you know that you are not alone. because you are then relating to another person who is thinking the same things and feeling the same things.”

Machines Of Our Disgrace is officially released this coming Friday, December 9th. It is totally worth the twenty-year wait. Machines of Our Disgrace offers up 13 new tracks of mind-blowing INDUSTRIAL MUSIC. If you ever got off on bands like Ministry, Skinny Puppy and Fear Factory, I feel very comfortable saying Machines of Our Disgrace will put a big fat 1990-era machinery-made smile on your face. Check out the title track here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gu5Z-FTRxRM If you like it, download a free MP3 of the title track and get a preview of the album here: https://soundcloud.com/celldweller/circle-of-dust-machines-of-our-disgrace.

facebook.com/circleofdustofficial

circleofdust.net

klayton.info

-

Music6 days ago

Music6 days agoTake That (w/ Olly Murs) Kick Off Four-Night Leeds Stint with Hit-Laden Spectacular [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock7 days ago

Alternative/Rock7 days agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Alternative/Rock2 weeks ago

Alternative/Rock2 weeks agoA Rejuvenated Dream State are ‘Still Dreaming’ as They Bounce Into Manchester YES [Photos]

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoTour Diary: Gen & The Degenerates Party Their Way Across America

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoThree Lefts and a Right Premiere Their Guitar-Driven Single “Lovulator”

-

Alternative/Rock2 weeks ago

Alternative/Rock2 weeks agoDeath Wishlist Are Fiery and Fierce with Their “I Get Bored” Video Premiere