Interviews

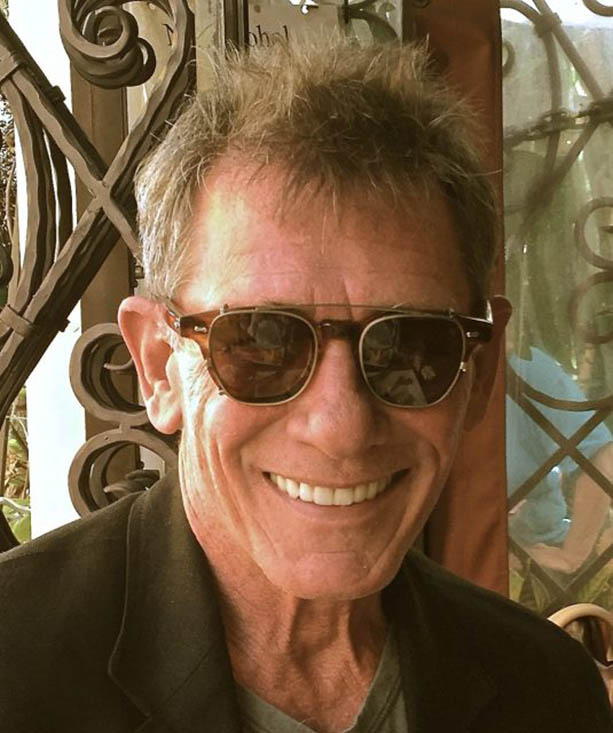

William Wisher Interview; Exclusive and Highly in-Depth Chat with the Legendary Screenwriter and Co-writer of ‘Terminator 2’

In this interview with screenwriting legend William Wisher, he dives into what it’s like to work with James Cameron, watching scripts become blockbuster movies, how the game has changed, and why he’s moving to TV.

William Wisher is a screenwriting legend for co-writing one of the greatest action movies of all time that’s also one of the greatest sequels ever made, Terminator 2: Judgment Day. On top of that, Wisher has gone on to re-write many action scripts that were in crisis while shooting had already begun. He helped craft some of these scripts into wildly entertaining movies including Die Hard With A Vengeance and Live Free or Die Hard among many others.

After being a successful screenwriter for over three decades, Wisher has seen Hollywood go through many changes over the years. Now he is currently working on a new action thriller TV pilot as his next project!

In this interview, Wisher dives into what it’s like to work with James Cameron, watching scripts become blockbuster movies, how the game has changed, and why he’s moving to TV. Hear how one of the best action screenwriters ever broke into show business, made a name for himself, and managed to create a career over the years that took a lifetime to build!

How did you first begin to develop your career in show business working with Jim [James] Cameron on his first independent film [Xenogenesis, 1978]?

Wisher: Well, Jim Cameron and I met in 1972 or ‘73 and he had just moved down here from Canada. He was enough months older than me that he graduated from his high school the year before. His parents moved down to a little town called Brea [California], where I was a senior in high school.

I was getting ready to graduate and I knew his girlfriend, who later became his first wife, Sharon Williams. It’s a very small town, it’s not too far from Disneyland in Orange County. She said, “Oh, you should meet my boyfriend, he’s really into movies and science fiction and all that stuff.” Back then it was really acting, I thought I wanted to be an actor. That’s what I was studying in school.

We were kind of growing up at the same time and trying to get into the business and I always enjoyed writing, but that focus came a little bit later. I remember Jim working on something and he’d say, “Hey, you’re an actor. Why don’t you come on over and say this?” You know, this line of dialogue or this and that.

I kind of slowly just got a little more interested in it. By the time I was in my mid-twenties I really got burnt out on the business end of acting. It’s just very brutal. I thought I was pretty good, maybe I wasn’t (Laughs). I didn’t enjoy the process of the business end of it.

So I thought, “What am I gonna do?” I’ve always had kind of an ear for writing but I wasn’t really trained at all. At that age, I didn’t want to go back to college for four years. I went to UCLA, I went to their creative writing department and I stole all of the syllabus’s [course curriculums] off of the professors doors and I went to the bookstore and I dropped a few hundred dollars on the books and I said, “Okay, I’m going to read these books and do the course work.” I attended some lectures if I could sneak in because they usually don’t bother to see who’s there.

I promised myself that by the end of this, I’m going to write a screenplay and I did. It was terrible, I don’t have it around anymore, but it had a beginning, a middle and an end. In doing that work, I read this book from the 1930s by Lajos Egri called “The Art of Dramatic Writing”. It’s like reading a Bible, it’s not a brief skim, but I learned so much from that. About story construction, characters, all that stuff. So I just started writing!

I helped Jim with Terminator one. He had written a treatment and asked me to flesh out some of the scenes and I did that. I really wanted to be an actor, that was kind of how we met before I started transitioning into writing. He went, “ I’ll get you a SAG [Screen Actors Guild Union Membership], you can play the cop.”

I thought to myself, “Why not get a SAG card?” The more options the merrier.

It’s better to have it and not need it than need it and not have it.

Wisher: Exactly! I had a lot of fun playing that guy and meeting Arnold [Schwarzenegger] and I did some other things. I did a TV movie for Warner Brothers, it was a Western. Then along came T2 [Terminator 2: Judgment Day], that was a different experience entirely. We [Will and James Cameron] were talking about working on something else together. He calls me and said, “I have some good news and some bad news.”

I said, “Okay.” He said, “Well the bad news is I don’t want to do the thing we were going to do.” I said, “Okay, fine.” He said, “The thing is we’ve finally got a direction for Terminator 2 and I want you to write it with me.” I said, “Great!”

That would be a game changer!

Wisher: Yeah, we spent the intervening six or seven years just kickin’ around, having fun together. We would talk about stuff from time to time like, “Well, what could it be?” So we had all the bad ideas already out of the way. We wrote the whole thing in about…we cut it out in about six and a half weeks, so it was very fast.

Because typically the development of a project of that size and caliber, budget and scale take at least six usually?

Wisher: Months?

Yeah.

Wisher: Minimum. Sometimes it can take longer. The way a film like that works, out in Hollywood they call them tentpole films, is the schedule is always done backwards. Jim said, “It’s going to take this long to shoot it, this long to edit it, so we’ve got about a month and a half for writing.” And I said, “Wow!”

So we sat down to write it. First, we wrote a treatment [outline] for it together. With Jim [Cameron], we kind of do the same thing, it’s kind of how I learned with him, kind of how we learned together. You just start putting ideas down on paper and you go, “Oh! This goes between this and this!” and you start to flesh it out. The treatments he likes to do are pretty long, probably about fifty pages.

Depending on the project I could imagine.

Wisher: So we wrote this side by side. Like literally taking turns at the keyboard and then we cut it in half. He took one-half and I took the other and we elaborated, turned it into screenplay form with dialogue and all that stuff. Then we traded halves. We went over each other’s work, then we put it together and went over it one last time for a couple more days. Then he put it in a briefcase and went and gave it to Arnold [Schwarzenegger].

Wow. Some people really thrive on that pressure. I can imagine that having that six months to a year would almost dilute that kind of process. Especially when you’re doing something as high paced and as highly anticipated to a really amped up action movie. Especially when it’s starring Arnold Schwarzenegger! Having that kind of pressure being on must have actually been kind of helpful.

Wisher: You know, honestly, I’ve never really been bothered by that kind of thing. To take six months or a year to write something that’s going to be one hundred and twenty pages long isn’t something you really need to do. Now often the process will go that long because you’re one, two and three drafts, and you’re giving it to studio people. Then they all have ideas, then you have to make changes, and so on. With Jim Cameron, it didn’t work that way because everyone says, “What do YOU want to do?”

By that stage in his career, you’re just dealing with him. It goes pretty quickly and in the 90s I was kind of a script doctor on a few different movies.

You have a pretty prestigious reputation for a lot scripts that you have to your credit, but also that you were un-credited in doing rewrites on. I’ve mostly heard rumors, not rumors about you, but about some of the movies you’ve worked on. I just wanted to make sure I have the facts straight, but didn’t you do some subsequent drafts of movie franchises like Die Hard and Lethal Weapon and things like that?

Wisher: I never worked on a Lethal Weapon, but I did two different Die Hard films. Number three and number four.

Okay, I just wanted to make sure I had that correct.

Wisher: Yeah. I’m not credited on that, I kind of rewrote everything from front to back. When it came to Die Hard three, Die Hard With A Vengeance, with Jeremy Irons. I had just come off of Judge Dredd, the [Sylvester] Stallone movie. Andy Vajna was producing Die Hard With A Vengeance and said, “Hey, do you want to do me a favor? Come to New York for a couple of weeks because I’m doing this Die Hard picture and it needs a little bit of work.” And I’m like, “Yeah, sounds great.”

I fly out there and John McTiernan (director) is on day five or six of the schedule. I was handed the script on the airplane before I went out and I thought, “Oh boy…” (Laughs). It’s a bit of a mess. So I get there and they’re set up in Central Park south doing the car chase. I went up when there was a free moment to introduce myself to John McTiernan, who I did not know.

I told him who I was and why I was there. I said, “Why are you shooting this?” He said, “It’s the only thing I know I’m keeping.” (Laughs) I said, “Okay.” So I kind of jumped into that with both feet and I met Bruce [Willis], and everybody else. We just sat down and I was trying to write faster they could shoot. I ended up working on that movie for over six months I think, all in.

Now, just to kind of bring us up to speed with where you’re at now. What was the major impetus around you wanting to make your next project a TV pilot instead of going back to the Hollywood studio system? Was it a force of leverage from a business perspective? Or was it just the nature of the idea? Was it too big to fit into one movie or even a trilogy? Was it just because you wanted to take a shot at it?

Wisher: Alex, there’s a lot of reasons. That’s a very good question. I guess the shortest answer is the studio system has changed. A lot of things they’re doing now are comic book based, and as interested in that stuff. Also, they’re making fewer movies than they used to. I did an independent film last year with John Moore [director] and Pierce Brosnan called I.T. that ended up on Netflix.

Quite frankly, most of the work I’m liking these days, I’m seeing on television.

I’m wondering what some of that work was that really caught your eye. What is it that particularly stands out to you right now?

Wisher: Breaking Bad, Homeland, Better Call Saul, The Night Of, it’s fabulous. There’s another show on I like a lot called Good Behavior. There’s so much television now because of the Internet, cable, and all of that stuff, there’s a lot of opportunity to do interesting work. Or work that’s more interesting to me personally than what’s going on that big studios are doing. I’ve been doing this for a long time.

My interests have changed, along with the years. Television is a place where a lot of those things are welcome there that are harder to set up at a studio.

You mentioned earlier that studios had changed. For somebody who has been working on high caliber projects with A-List stars and top-notch directors, how have you perceived studios to have changed while working alongside them?

Wisher: They’re making fewer pictures.

Do you think it’s tentpole pictures being so expensive they swallow up the budgets for middle-of-the-road pictures?

Wisher: I think so. They’re looking to make the safest bets possible. So they’re rebooting older films, they’re franchising, they’re all sequels, and Marvel comic type stuff. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, I’ve done sequels myself. There’s less new, original work being produced than even fifteen years ago.

Also, there’s been a vertical integration among studios with how the distribution platforms are. It’s changed. In the other world you can jump into, the independent film world, I’ve dabbled in that twice now. You can do very interesting stuff there, but financing is always difficult. It can take forever to get something finally financed and put together. Whereas with studios, if they wanna make something, they just make it.

They don’t mess around. You don’t have to go around begging and trying to get money here and money there. Really, the main reason with TV is the content you can put on it, the content you can create for it and the fact there is so much of it right now. I just find it interesting. It is kind of where my head has gone.

I’m not alone in that. There are a lot of guys that have had careers in film that want to work in television as well.

Since technology has rapidly advanced and evolved so much, especially over the last ten or twenty years, do you feel like the storytelling in Hollywood movies is struggling to keep up with how they pull things off visually? Just to use your work with James Cameron as an example. He’s got a huge reputation for being innovative with the way he uses technology. But it was always within the context of the story, so do you think it’s a matter of one trying to catch up with the other?

Wisher: Wow, I didn’t think about that. Just to circle back to Jim Cameron for a moment, he’s an exceptional filmmaker. There’s not anyone else quite like him. Jim has always been character and story driven. However, he LOVES 3D and CGI technology, he’s wrapped his arms and his legs around that. To Jim, those are simply tools for how he wants to tell the story, it’s all about the story with him.

There’s a lot of formulaic stuff going on in giant tentpole studio films. Where, “The story has to do this and the story has to do that, and we’re going to have these effects in it.” They don’t all have Mr. Cameron’s mind, which is a remarkable mind.

They’re making fewer films and they’re spending more on each one. That’s how they’re seeing their business model. That’s what they want to do.

Now, diving right into your pilot, I know you can’t talk too much about it. What was the most exciting part of sitting in front of the blank page and shifting gears into that different dynamic? Where you’re not confined to a two-hour format, there’s all this extra gas in the tank and no roadmap, so you can take the story wherever you want?

Wisher: That’s an excellent question. The main difference is, a great television pilot sets the table. You introduce the characters, you introduce the situation, you let the audience know what kind of vehicle this is, and you end it in a way that hopefully makes someone want to watch the next thing that happens.

It leaves something to be desired.

Wisher: Yeah. Now, in a film, in a one hundred and ten or one hundred and twenty pages, you’re telling a whole story. You’re creating the whole world and you’re bringing the characters in, and you’re bringing that story to a conclusion.

In a TV pilot, you’re just setting the table. Here’s the road we’re going down, here’s who’s going to be sitting in the car with us, let’s go.

One of the things, in terms of learning how to think differently, is when I’m working on a film, I’m thinking of how I’m going to bring all of this to a conclusion. In television, I think the main difference is you want to keep the story going and the characters engaging, without giving much away.

You have to look at a season as an act arc. Instead of three acts, everybody wants five, because they want you to do five years of whatever the show is. Today what I’m seeing on TV is, keep everybody engaged, but slow it all down, in terms of the story.

Unwind over a much longer period of time, so you don’t always have to think about closing loops constantly as you do in film. But you need to know where you’re going.

The focus has definitely got to be there but I find the experience is about savoring the flavor. Really soaking in the moments than squeezing blood from a stone at every turn.

Wisher: Yeah, it’s all character driven. It’s a lot more people talking. I love doing character work. In film work, it’s almost like journalism. I did a little bit of journalism really, really early on, and they paid you by the word. But also, there’s only so many words you get paid for. So you have to be very precise and very concise.

When I’m writing a scene in a film, I try to convey the absolute most in the least words possible.

Details seem to be essential.

Wisher: Yeah, and you want to be extremely stingy towards writing the most out everything. You want to keep things moving. Moving, moving, moving, to evoke the absolute most with the absolute least that you can. TV is a lot more like a novel.

You can write scenes that are longer than what you would put in a film and you can write more of them. There are scenes you would cut from a film because they’re not absolutely essential, in television, it’s a different kind of essentiality. You can spend a lot more time on characters, on what they’re thinking, on what they’re going through.

You’re really pushing resolutions way, way out, you don’t want to get to them for a long time. So it’s sort of the opposite in that respect of how you would think of a film. What I also hope I can bring, because this is also what a lot of film guys transitioning into television want to do, is bring a cinematic or film sensibility to the format.

It’s all changing so rapidly that I don’t know how long it will be before the only theaters that exist are going to be IMAX 3D theaters. Because there’s War Machine, the new Netflix movie, and it looks really funny, looks really good.

That’s a feature film with a big movie star and it’s going to be on VD . The same thing with I. T. with Pierce Brosnan, that was done for Netflix.

It’s not like he’s an unknown or some handsome guy. He’s an A-List actor. He was James Bond. (Laughs)

Wisher: Oh yeah. He’s wonderful to work with, we had a lot of fun. The point that I was getting at is that the line between film and television is getting very gray and fuzzy. If places like Amazon and Netflix are going to make features that are only going to get a television release or films that are specifically downloadable, the distinction between film and television is just going to go away very quickly.

It may take a decade, but you might make a three-part film. Is that a television show or is that a movie with two sequels? (Laughs)

Given the nature of how quickly technology is advancing, who knows? Do you find that it’s easier for audiences to connect to material when it’s straight from the creators without a studio in the middle per say?

Wisher: I don’t really know the answer to that yet. I don’t think we know yet. It’s certainly much easier, not just because of the technology and distribution. But because you can go buy a computer for a few thousand dollars that can create special effects and edit an entire film.

It’s possible for someone with a great mind and vision and very little money to create something special that will only be available for the internet. The danger of that single auteur format is that often it doesn’t work very well because it’s like a novelist who has no editor.

If the novelist is brilliant, okay fine, maybe they don’t need one, almost everybody does. Good producers are worth their weight in gold. They’ve always been, the really great ones, have always been a rare breed. I think not having too many cooks, but a couple of voices, people that you know and trust that have good taste, to collaborate with you is super important.

It makes the work better. It’s really a rare animal that makes good work without anybody that they respect. They need a good producer to tell them, you need more here and you need less there.

The last question I was going to ask you was, I know there’s not too many details you can dive into but, is there anything you can tell us about your new show?

Wisher: I’ll tell you that the world it’s set in is an espionage world. It’s a thriller. It’s set in modern day and it gets into a lot of the paranoia of not knowing who is doing what to whom anymore. It’s not a political show in any way, but it’s an espionage show. Everyone is trying to figure out what the hell is actually happening.

I think the world feels like that to people these days. It’s kind of in that vein.

I’m sure it leaves something to be desired. I know action is your forte.

Wisher: Oh, there’s action in it!

I bet there is! (Laughs) If your name is on it, I guarantee there is. I really appreciate you sharing your time, energy, focus, and expertise Will.

-

Music5 days ago

Music5 days agoTake That (w/ Olly Murs) Kick Off Four-Night Leeds Stint with Hit-Laden Spectacular [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock7 days ago

Alternative/Rock7 days agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Alternative/Rock2 weeks ago

Alternative/Rock2 weeks agoA Rejuvenated Dream State are ‘Still Dreaming’ as They Bounce Into Manchester YES [Photos]

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoTour Diary: Gen & The Degenerates Party Their Way Across America

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoThree Lefts and a Right Premiere Their Guitar-Driven Single “Lovulator”

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoDeath Wishlist Are Fiery and Fierce with Their “I Get Bored” Video Premiere