Alternative/Rock

Tuk Smith and the Restless Hearts: “Every day I wake up and I don’t feel like I belong on this planet”

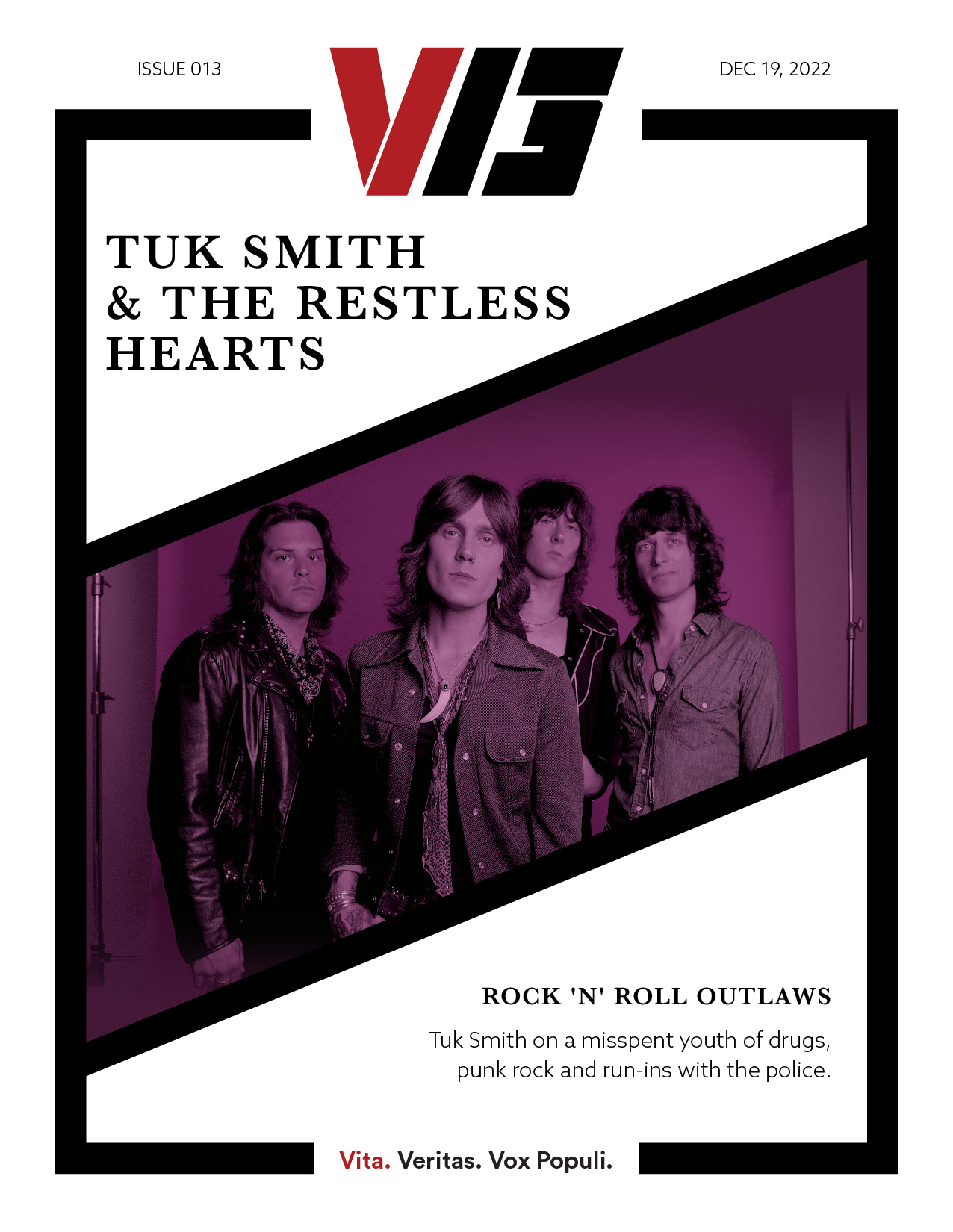

American rock singer Tuk Smith (Tuk Smith and the Restless Hearts) talks openly about his tough childhood, drugs, rebellion and more in our latest cover story.

The first time I spoke to rock singer Tuk Smith, back in early 2020, you could tell this was a man who had his scars. By his own admission, his life story includes a tough childhood, rebellion, drugs, alcohol and, of course, music.

The ride didn’t get any easier as his band Biters split up; the pandemic put pay to not only the release of his album but also the opportunity for Tuk and his band to go out on tour for the original run of dates on the Def Leppard and Motley Crue tour. Still, they say you can’t keep a good man down so, through it all, the singer has turned to the one constant in his life, music and armed with a notebook and a ton of stories, sat about working on the just-released collection Ballad of a Misspent Youth. (Read our full album review here.)

Following the release of the album, we sat down with Tuk to talk about his childhood, his experiences and some of his memories.

Hey Tuk, how’s it going? Before we start, last time we spoke, you were in Atlanta, but I see you’ve relocated to Nashville; what took you there?

Tuk Smith: “Yeah, I’m in Nashville now. It’s better for being a producer and songwriter. Atlanta is the hip-hop capital of the world. That doesn’t matter, though. What happened was my neighbourhood started gentrifying, and, I know that happens in a lot of cities, they tore down things like my favourite breakfast spot and put up a chain place up. I was having an emotional response to it. I was leaving my house and getting mad. I grew up in Atlanta and kinda needed a fresh start. Here, if I woke up and they’d put a Mcdonald’s next door, I wouldn’t care as I have no emotional attachment to it.”

“My stepdad epitomized everything I hated, so to rebel against him, I got into punk. I got into music.”

Going right back, what were those early days like?

“I came from a really small town. I had a really hard upbringing and childhood. My stepdad epitomized everything I hated, so to rebel against him, I got into punk. I got into music. He would call everything I listened to a homophobic slur. How I dressed. Homophobic slurs. Anything as a ‘fuck you’ to him, and anything in that society was what I gravitated towards.”

Growing up in a small rural town, what were you rebelling against?

“It has nothing to do with the people. This isn’t me hating on them. That place is just designed to keep you where you don’t have any dreams, and you stay there. You don’t question anything. It was religiously narrow-minded. It was very economically limited and very culturally limited. I wanted out.”

At what point did you want out?

“Yeah, very early. I hated where I was at. To this day, I feel like a fuckin’ alien. Every day I wake up, and I don’t feel like I belong on this planet, but you can imagine, as a teenager, even before that, you’re just really traumatized by this person, and you feel even more like an outsider. I’ve always felt like an outsider and I think that is why I was attracted to rebellious music. I think that a lot of musicians feel like outsiders. I’m not special, but I had a calling, a ‘fuck you’ for the establishment.”

What were your dreams growing up? What could you see yourself doing?

“I was taught to never dream but to work at a factory or maybe go into the army or go to jail. So, to me, going where the party was. I didn’t think I had a future. I just wanted to party. I was an alcoholic in High School. I took pills. I took as many drugs as I could. There was no foresight.”

Were there no boundaries for you growing up?

“Well, I moved out when I was seventeen, and I was always playing in punk bands, and I looked so fuckin’ crazy in my hometown that the only place I could get a job was in Dairy Queen, but they fired me. They were Hindu, and they were a lot more open to how I looked with the piercings and the hair as opposed to the fuckin’ rednecks down there. I then got a job in a Pizza place. I lived in a loft with five or six people and played in a punk band. I was blacklisted in my hometown, and they were trying to put me in jail, so I had to leave. I had the S.W.A.T. team kick in the doors of my house. It was very unhealthy. It was fun, though.”

I know I discovered bands like Motley Crue through tapes from school friends. How did you discover punk rock?

“Skateboarding. My dad hated skateboarding. He hated how they looked. He talked shit on them, so I gravitated immediately to skateboarding. They were into anything from the Adolescents to Rancid to The Offspring to Black Flag. Any of that kind of stuff was a gateway into guitar music. My mum always listened to music before her time. She liked AC/DC, Tom Petty, CCR, which now are my favourites, so I was always raised around classic rock as she always had it on.”

I’ll never change. It’s in my DNA. So to me, it was a ‘fuck you’. We had to wear uniforms at school and I would have ‘I’m in prison’ and a number written across mine.

Is there a band you gravitate back to that takes you back to that period in your life?

“I don’t know because I’ve listened to so much music since then. I’ve been in the studio. I’ve travelled. My palette is so much wider now. Bands that have stuck around all my life have been bands like AC/DC, The Clash, and bands like that. The stuff that transcends everything. Some of those bands definitely have stuck with me.”

Was there a lightbulb moment where you thought this is for me?

“There have been eras in my life. I mean, when I first heard Cheap Trick, I thought it was the Sex Pistols. I couldn’t tell as a little kid. It was on classic rock radio. That band and then the Sex Pistols. My stepmom, who I lived with at the time, gave me a Sex Pistols tape, and I could play that shit. I couldn’t play Led Zeppelin or Skynyrd or those long-haired guitar guys, but I could play “God Save The Queen.” I was so beaten down by that point, I didn’t believe in myself, but I knew I could spit and play fuckin’ power chords. That’s why I gravitated towards it.”

Do you remember your first band?

“Yeah, it was called The Downtrodden because I was so oppressed [laughs]. You know when you’re a teenager, and you think the whole world is against you?”

I do. I’m fifty, and I’m still like that now…

“Exactly. I’ll never change. It’s in my DNA. So to me, it was a ‘fuck you.’ We had to wear uniforms at school, and I would have ‘I’m in prison’ and a number written across mine. I was always suspended. I was always at in-school suspension. I was expelled several times. I got expelled from school for inciting a riot.”

Any regrets?

“[laughs] Yeah. I should have gone to college for coding or some shit.”

I grew up in a small village with no music scene. What was it like for you as a kid? Were there places you could go to see bands?

“There were little train depots, local shows in the Legion halls. My band in high school was very active. We played in skateparks. We practiced every day. It was my entire life when I was fourteen or fifteen years old. I got to High School and put together a band. We were rehearsing and playing. We recorded a six/seven-song record; I don’t even know where that is, but, yeah, it’s been my whole life.”

Do you remember the first concert you went to?

“It was probably a local punk rock show with like five or six bands, and those kinds of shows change your life. It was the only thing I thought I could do. It was the only time when I felt free.”

Artwork for ‘Ballad of a Misspent Youth’ by Tuk Smith and the Restless Hearts

Was there a moment when you realized you wanted to be a singer in a band?

“It was just one thing that led to another. I never thought I was going to be a songwriter or a singer ever. I was kinda where I couldn’t find anybody to do it. When I started writing and singing, I had very low expectations and goals. Maybe tour regionally. There was no thought for the future forever. It was just party to the fuckin’ max. Then, when I started writing a couple of songs, people liked them, and I really felt like I had something to prove; it’s that chip on my shoulder that has fuelled me my whole life. All the police, all the people in the town that told me I was a punk rock piece of shit, that was defining.”

What about their attitudes to you now? Has that changed? Does that “fuck you” feel right?

“At this point, no. Probably if it came earlier. By this point, I’d been through the wringer so much that I’m just completely humbled and thankful that I get to do stuff. I’ve got a fight in me, but it’s a different kind of fight. I didn’t get the sweet victory of a fuck you, but that’s okay, though.”

When did you notice that fight change?

“There’s just been a succession of really bad luck and hard times. A lot of personal turmoil. Every little thing that happens to you, you can either be bitter, or you can be humble. I’m still a work in progress, man, and I feel like a lot of musicians are. If we were normal people we would be normal people, and we’d be working in an office. Of course, I’ve got issues to work through and for a time, that was drugs and alcohol and trying to push it to the limit. When I was watching some of my friends die and go to jail or I was on probation or getting arrested, there started to be that wake-up call, and I realized I had to change, or I was going to die.

“I know it sounds very cliche, but it was real. It wasn’t glamorous. It wasn’t like a Nikki Sixx autobiography. I was washing dishes when I started Biters. I was broke. I’ve always been poor. I’ve always had a support team and mentors and people to help me, but I’ve also always self-sabotaged that because of that fuck you. When I noticed that I changed my lifestyle. I quit drinking, and I quit doing drugs and just got into healthier habits.”

How difficult was that to do?

“Horrible, dude. It was like a rebirth. Honestly, I wanted to change my DNA because I didn’t want to be who I was born into.”

You talk about Nikki Sixx, and there are similarities where he changed his name and his identity, but it certainly wasn’t glamorous, no matter how big his band was. What did you learn from your own experiences?

“Oh, I’m still learning. At this point, I’ve learned a lot. Every fucking year I’m trying to be self-aware. I learned how I should have conducted myself better or how I could have done something differently, or should have trusted my gut instinct. To me, if you’re trying to better yourself and not be a self-obsessed narcissist, try to be good to the people around you, try to be a good friend, try to be a good person. That’s where I’m at now. That doesn’t mean I don’t have my bad days and say some fucked-up shit, but it’s few and far between.”

I’m still a work in progress man and I feel like a lot of musicians are. If we were normal people we would be normal people and we’d be working in an office.

The new record is you writing your stories. What did you get out of that? Was it a happy experience revisiting those stories, or was it a cathartic one?

“I think most of the things I’m doing personally; I don’t know I’m doing until after the fact. In retrospect, I can look back and see how that was fucked-up or how it was awesome. I think writing this last record was to prove to myself that I could write another record because one had already been shelved. When I had to break up Biters and go solo, a lot of people told me not to do it, they acted like I couldn’t do it.

“I felt very alone at that time apart from a couple of friends, then when the pandemic hit, I felt bitterly alone. I lost my record deal. I lost all my tours. My record was shelved. I was basically back to where I was before I started Biters, except for the fact that I was quarantined apart from a piano and a guitar.”

We spoke first at that time; since then, what has been the most important lesson you’ve learned?

“Right now, I’m celebrating all the small victories, and I’m really grateful for every small thing because it was so damn hard getting this record out that I’m so grateful. That’s more of a deeper lesson. A daily lesson I’ve learned is not to send emails when you’re pissed [laughs]. I say fucked up shit, and I’m really proud of myself lately.”

We’ve all done it, and you know you’re going to do it again…

“[laughs]. I have to write it down now and give myself twenty-four hours before I send it. I’m tired of apologizing.”

Going forward, then, what are your goals in life?

“As a musician, I would just like to be a great songwriter, and I want the songs I write to be loved and appreciated by people. My goals are to go out and tour and play for a bunch of people and be a working musician and create art. That’s the only thing that fulfills me.”

Just to wrap up, then. Going back to your teenage years, what one piece of advice would you give yourself?

“If I could go back to my six-year-old self, I would tell myself to believe in myself because I didn’t. I would tell myself to write songs and that I could do it. It’s not rocket science. That’s the only thing that I wish that I had started earlier. I know it sounds cheesy, but if I could go back it would be that… to believe in myself.”

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoTake That (w/ Olly Murs) Kick Off Four-Night Leeds Stint with Hit-Laden Spectacular [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock2 days ago

Alternative/Rock2 days agoThe V13 Fix #011 w/ Microwave, Full Of Hell, Cold Years and more

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoTour Diary: Gen & The Degenerates Party Their Way Across America

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Indie2 days ago

Indie2 days agoDeadset Premiere Music Video for Addiction-Inspired “Heavy Eyes” Single

-

Alternative/Rock2 weeks ago

Alternative/Rock2 weeks agoThree Lefts and a Right Premiere Their Guitar-Driven Single “Lovulator”