Alternative/Rock

Steve Vai: “You can make a particular statement by the dynamic of the whole record”

Insights into the man who creates some of the tastiest guitar licks on the planet, plus his latest album ‘Inviolate.’

Earlier this year, Steve Vai released Inviolate, his new studio album on Favored Nations/Mascot Label Group. In many ways, it’s a reactionary album to the pandemic in that it was both and approached differently than any of his previous releases. Over 40 years as a composer, Vai has routinely delivered incredulous guitar stylings with a panache for providing mind-bending compositions, with an end effect suggesting anyone can do what he does. If you were to ask 20 people to name the best living guitarists on the planet, there’s a good chance Vai would wind up on all 20 of those lists. His technicality as a player is already the stuff of legend.

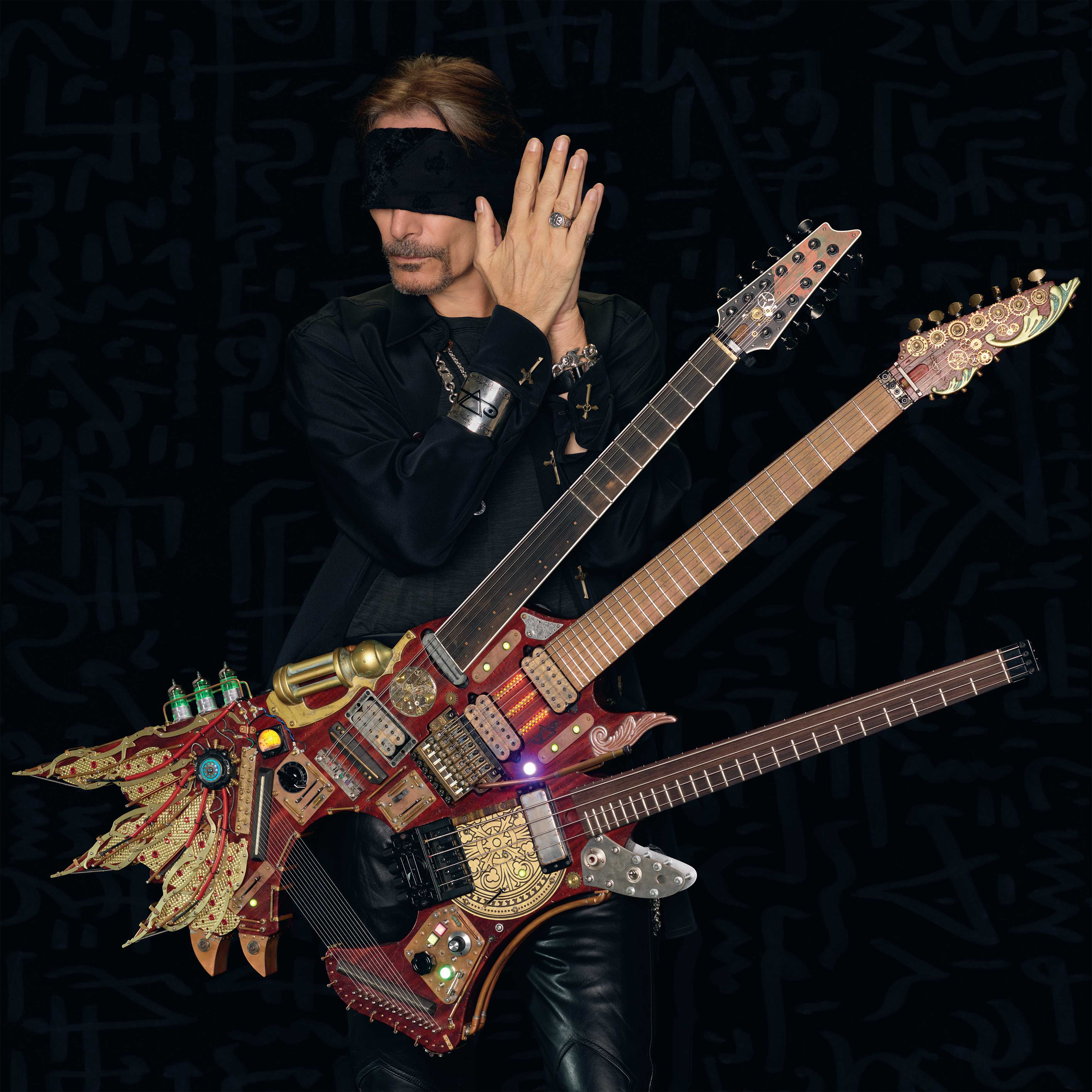

Inviolate features the lead track “Teeth of the Hydra,” a composition Vai wrote and recorded with a one-of-a-kind custom triple-necked guitar he coined the Hydra. It’s a track that couldn’t exist without this incredible customized instrument. He spent over a month of full days composing the track on the Hydra, unlearning the things he knew about playing a traditional guitar and slowly mastering the new instrument.

“After a while, I felt like I was entering new dimensions even in my playing because your mind changes, and when that changes, your expression on anything changes.”

Shortly after the release of Inviolate, Vai was set to head out on the road for a lengthy U.S. tour featuring more than 50 dates. The pandemic cut those American tour dates short, and they were rescheduled for this fall. After our conversation, Vai said he intends to come to Canada in 2023 and tour here at as many venues as he can book. He’s recently been over in Europe doing some live dates and is eager to get out on the road this fall and showcase Inviolate on his home soil. Watch his website and socials for those announcements down the road.

We thank Steve Vai for taking a healthy chunk out of his afternoon last week to field a few questions for V13 via Zoom. The audio (SoundCloud) and video are available here if you’d prefer to hear Vai’s answers in real time.

You’ve been touring. How has that been for you?

Steve Vai: “Well, you know, it’s interesting; we did a European tour; I had to postpone my American tour, which was scheduled first, and it’s the first tour in six years; it was wild. A lot has happened. And I wasn’t quite sure how it was going to go, but on a performance level, it was great. As soon as I got back out there and hit the stage with the band, we just lit up, and it just felt really comfortable, and I realized, ‘how could I have let so much time go by?’ We had done gigs and stuff, but a tour is kind of different. There were a lot of challenges because of a lot of issues.

“A lot of bands from 2020 to 2021 and 2022 had to move their tours; it seems like they all moved to the summer festival circuit in Europe in 2022. So there were unexpected things like, (and I heard this from everybody), when you let a bus sit for two years with no love, they had all these issues, and it was so difficult to find gear, to find workers, to find buses. All the things that we take for granted when we tour. And just so many other little obstacles; closed roads and flat tires and no air conditioning, the crazy long drives. But that’s all part of the territory, and it was good to kind of go through that gauntlet because now, any other tour that we do here in the States or elsewhere, it’s going to be a piece of cake.”

To pull from your analogy, sometimes, when you let a bus sit for two or three years, it gets some rust on it as well. Did you guys feel rusty?

“Yes, because when you get on stage and the lights go down, and you’re in the heat of the moment, everything changes. You could rehearse all you want; you can sit in your bedroom and know the songs and learn them until you’re blue in the face. But the moment you hit the deck, I know, at least for me, the whole story changes. So there were certain idiosyncrasies that a guitar player like myself might have when you just hit that stage; like I’ll grab the whammy bar differently, I’ll go for certain things. And usually, your chops aren’t as refined as when you’re on tour for a while because that’s real. And for me, it takes a couple of weeks to settle in, for my fingers to settle in, and for my body to get into the flow of a show.

“So those things, yes, they were rusty, and I didn’t know what to expect. And I noticed a few things because of six years. One of the things that happened in those six years was last year, I turned 62, so things change, and you go with it. I discovered that I organically kind of went with it, like I may not be running around like I used to.

“I keep everything, And the demos sometimes are just like me sitting on my bed at night with an unplugged electric guitar, coming up with a riff.”

“I saw some video clips of mine; we just posted a little something from 2000, and I was just, I looked like a helicopter, you know? It’s like all of these; (mimes his arms akimbo). And when I got out on stage on this tour, it was much more refined. My attention is really so much more on the notes. So there was a change, and there was a lot of rust, and it took a little time to blow that out, but surprisingly for me, everything was working great. After a while, I felt like I was entering new dimensions even in my playing because your mind changes, and when that changes, your expression on anything changes.”

V13 Cover Story 004 – Steve Vai – Aug 30, 2022

You put an album out during the pandemic. Have you been describing it as a pandemic album? Is it something you put together entirely during lockdown?

“Yeah, it came together during lockdown, and I guess the term pandemic record refers to certain parameters, such as I was stuck in the studio alone; I was sending files out to other musicians to be worked on, and this turned out really good actually. It was great. I wasn’t there to tell them everything to play, and so a lot of the record. A lot of the other performers that did that with me, I would just say, ‘you hear the track; give me what you think.’ And, of course, there’s certain things you have to work within, but I got some great stuff back. The lockdowns and the pandemic has affected people differently. There’s no one way. Of course, a lot of people suffered, but some people thrived. I was one of those people that just thrived like crazy because, of course, I was in a position where my economics are set up from past work so that you get enough to feed the beast.

“But it was the open time and ability to focus on certain things that I had always hoped to but never could really find the chunk of time to do, like the song ‘Candle Power’ that took a long time because it was techniques in it that were pretty obtuse to me. And then something like ‘Knappsack,’ which is a piece that I played with one hand because I underwent shoulder surgery. That was another thing that perhaps because I was in lockdown, I was able to navigate that, and then ‘Teeth of the Hydra,’ I play this triple-necked guitar with these harp-strings, it’s a wild looking instrument (the Hydra), and I composed this song on it that requires some crazy navigation; I looked like a whirly-bird or something, and that required six solid weeks of undisturbed 15-hour days. And that wouldn’t have happened if the situation wasn’t what it was.”

“The original inspiration for the look of the guitar came from a Mad Max movie.”

Talking about that guitar, there are elements of Inviolate that you probably wouldn’t have been able to make if you did not have that custom triple-necked guitar manufactured for you, am I correct?

“Well, I wouldn’t have been able to record ‘Teeth of the Hydra.’ That’s the only song I used it for. But yeah, that’s an example of the instrument kind of dictating the song. On several levels, because when I looked at the Hydra when it was completed, just the way it looked, that creates a ‘What kind of song is going to be played on this thing’ vibe, you know?

“And the fact that I refused to not use every neck, every string, I wanted to incorporate all of the potentials that I could into that song on that guitar. So it was completely different than approaching any other kind of song because I had to break like 50 years of habit. When you’re playing a guitar for 50 years, you hit a note, and your pick hits the string; it’s one of those kinds of things that you develop. But with the Hydra, all bets are off. I had to undo that conditioning so that I could navigate different things, almost like with a split mind, well, not almost, but yeah…”

With a split mind! It looks like a weapon. That guitar looks like something from a James Cameron movie.

“The original inspiration for the look of the guitar came from a Mad Max movie.”

How close to the final version of that Hydra guitar is it to the first prototype that Hoshino showed you? Is it close?

“It’s sort of close. I called the prototype the Hyena (laughs). We did that because it makes sense to do it because you don’t want to go through all the work of building the Hydra and finishing it, like the finishing and of all the electronics, everything without having something to try and go, ‘Ok, let’s move this neck this way a little bit. Let’s bring the strings here down over here.’ So the prototype is a good way to feel things before jumping into the fire.

“So one of the things that’s very different is the 12-string neck of the Hydra originated as a 10-string neck, so it’s five strings that are doubled because I thought, Well, this instrument is going to be unique. Let me do something different instead of having 12 strings, let’s have a 10-string neck. And I got the prototype, and I played the 10-string, and I said, ‘This is stupid; I want 12.’ That was one of the advantages and one of the differences between the prototype and the actual Hydra. And everything’s changed a little bit, at least from the prototype.”

“I think, ultimately, a part of what I do has to revolve around conventional commerce.”

I don’t know if you can actually answer this specifically, but what does a Steve Vai demo sound like? How close to a song like “Greenish Blues” is what you first noodled out compared to what we hear on the album?

“Probably about 80 percent is the same melodies and the same thing, because ‘Greenish Blues’ was something that just happened instantly and organically at a sound check. But the recording wasn’t great, but I was so moved by what was played that I decided that there’s a melody there, there’s an arc to the solo, and there’s riffs that just came out really nice. They need a little tweaking, so I’d say 70 to 80 percent.”

Artwork for the album ‘Inviolate’ by Steve Vai

Can fans ever hear any of your demos? Do you ever put any of those stems out so that people can check them out and compare?

“No (laughs). I keep everything, And the demos sometimes are just like me sitting on my bed at night with an unplugged electric guitar, coming up with a riff. That’s probably the other half of the songs on Inviolate stem from that. And I’ve got thousands of those dating back to when I was 13. Just little snippets. And it’s a great thing to do because sometimes it’s not uncommon to feel inspired and then have dry periods.

“So I notice that when I capture something that feels like it’s got a little energy in it, you know, like the melody to ‘Zeus and Chains,’ or ‘Little Pretty’; the whole ‘Little Pretty’ thing. I mean, most of the stuff it starts at as just a tiny little couple of bars sometimes, but it’s got the DNA of the entire piece in it, like you can hear it and go, ‘Ok, I know exactly where this is going to go.’ But then I put it on the shelf, and it has to wait its turn.”

Do you think that you’re always going to be an artist that seeks to make an album? And by this, I’m talking about putting together an entity of songs and calling it an album compared to maybe coming up with two or three songs and just putting them out one song at a time and foregoing the whole album process.

“Well, that’s a good question, and I’ve thought about it a lot. I think, ultimately, a part of what I do has to revolve around conventional commerce. Like you put out an album because then it’s a group of songs and it’s new, and it’s all there, and you can make a particular statement by the dynamic of the whole record; the instrumentation you use, who you’re working with, all of these things can create a whole package, which is nice, you know?

“But I do like the idea of, ‘Hey, I just recorded a new song; here you go!’ You know, like one song at a time, even, or two songs at a time, it’s a little more difficult in the way of promoting and touring and things like this. There’s a protocol that works pretty well, and it’s like, ‘Here’s a record. Now I’m going to go to tour and play it.’ I think eventually, from people like myself, I might do away with that and just do a song, put it out, and then when I want to go on tour, I go. It’s hard to say.”

I mean, you can amass those songs and put them out as an album; I don’t think it really matters. People will still buy the product.

“Well, they’re going to listen to it one way or another, if they’re interested in it, that’s for sure. The way that we create music, record it, distribute it, and even listen to it has changed dramatically, just since yesterday, just a couple of decades ago, and it’s continuing to evolve, and this, I think, is great. I try to embrace that evolution to serve me, and it does. So where it goes, I’m not sure, of course. But I’m going to take the best of wherever it goes and use it to my advantage, as I hope anybody would.”

“When people think of conventionally what a band is, it’s almost like the unconditional acceptance of everybody’s contribution.”

As you should. Now you mentioned that you put together Inviolate isolated and separate. Did you ever get an opportunity to be in a room with Bryan, Philip, and Henrik and put some of your pieces together while you were recording the album?

“Well, what I usually do is I create a blueprint, which is sort of like a demo that then gets built upon to be the final. That was for Inviolate because, you know, I didn’t really sit with the band and cut tracks. So something like the drums; A lot of the drums were done by Jeremy Colson, and we recorded those at Studio 666, Dave Grohl’s place, a great room! And then some of them, like a ‘Candlepower,’ I sent that out to Terry Bozzio, and he just did a fantastic job. And ‘Apollo in Color’ and ‘Sandman Cloud Mist,’ they were sent to Vinny Colaiuta, and he just returned spectacular stuff. And Bryan; ok, so here’s a good example; he played on ‘Little Pretty’ and that song is a beast, it’s very deceiving, it’s not something that I felt I could just send to anybody and just say, ‘here, play a part on this.’ There is just too much.

“So he came to the studio, and I worked with him directly on that. But then some of the other tracks Philip did, and I sent them out, and then the one with Henrik and I sent that out to him in Europe, and then he just did his thing, and I got it back, and I was like, ‘Wow.’ It was like that with everybody. You know, maybe there was a few where I said, Well, in this bar and this bar, can you do this? So I’d send it back and then (snaps fingers) you know.”

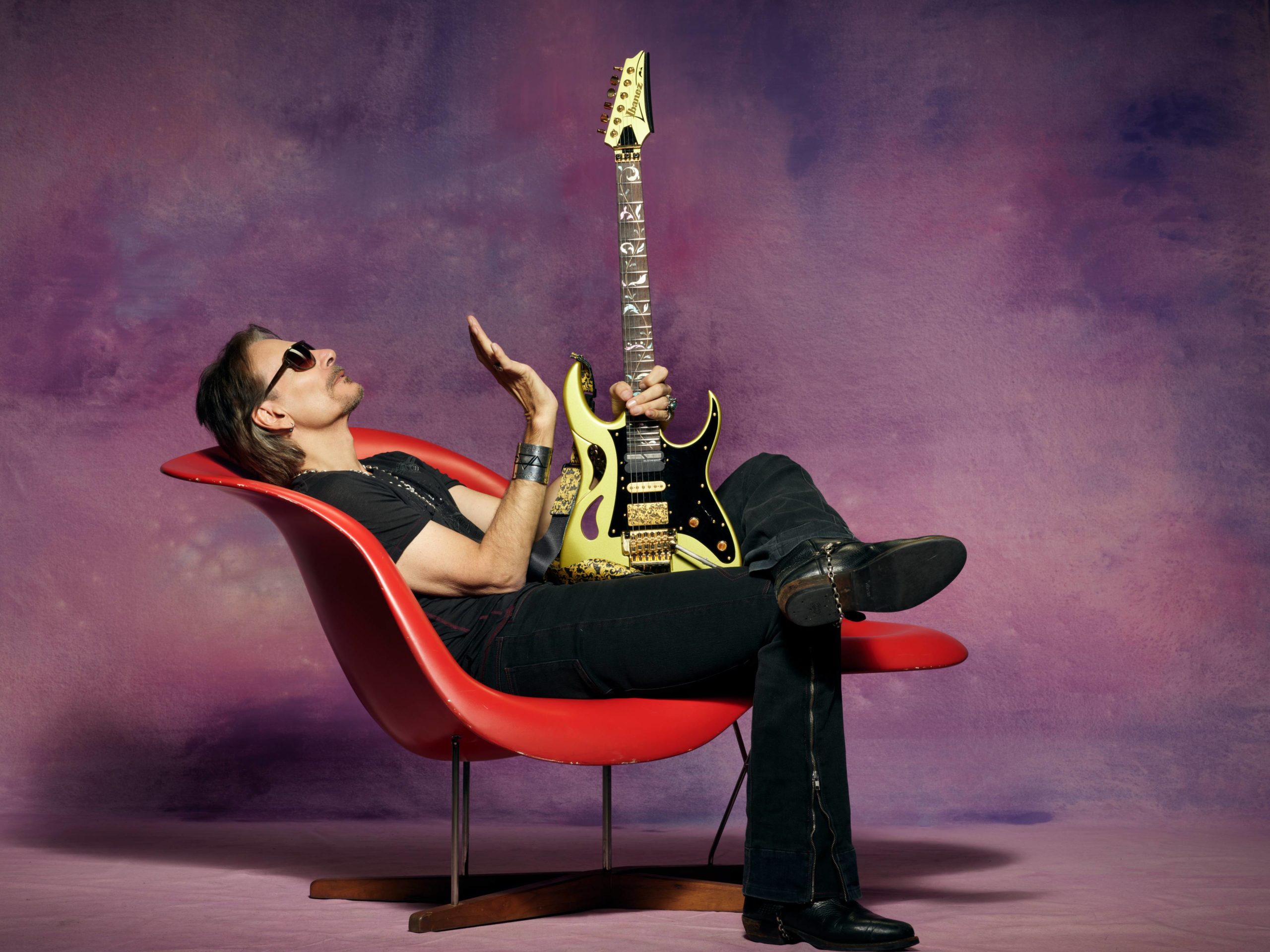

Steve Vai with gold guitar in 2021 by Larry DiMarzio

You mentioned Terry and Vinnie; your long-time fans will also get to hear some Billy Sheehan on this record as well, and it’s got to feel like a class reunion to you getting to work with these guys again. I mean, you guys must have a shorthand.

“Yeah, it’s really nice. Well, with Billy Sheehan, he recorded that bass track for ‘Avalancha’ back during the Real Illusions days. I had that track on the shelf; I just had the bass and the drums, and it was one of those songs that was calling to me. And having an opportunity to work in the atmosphere of Terry Bozzio and Vinny Colaiuta was really nice because, yeah, we go back to the Zappa days, and they’re just fantastic musicians and guys. So it worked great.”

All of your albums tend to sound unique. I like the sound of Inviolate, and I’m curious if you would maybe embrace doing another album in the same fashion where you maybe are not in the room together and you just sort of put your pieces together and assemble them. It seemed to work on this album.

“Yeah, it did work. And there’s elements of it that I really like. It simplifies things, and it also allows the music to be sprinkled with more uniqueness. When people think of conventionally what a band is, it’s almost like the unconditional acceptance of everybody’s contribution. It’s like; I saw this little interview with Keith Richards recently, and he said, ‘I can’t even imagine walking into a room with a bunch of musicians, and I have a guitar part, and I start telling the drummer what to play and the bass player what to play?’ That’s inconceivable to him. That’s the way I work. I tell everybody virtually exactly what to play because, for the most part, I’m a composer. I’d started out, before I was playing the guitar, I was writing little black dots.

“And that’s just one way of doing it; you manifest a vision. But for something like a lot of the rock music stuff, I will just say, ‘Ok, here we are, and we’re in 4/4, and here’s what I’m playing: what have you got?’ And everybody contributes, but if something isn’t working to my ear, I’ll jump in and make suggestions or make changes. That’s one approach. Another approach is, I hand a rock musician a piece of music to play and say, ‘play this exactly the way it’s written,’ because that’s how I hear the entire piece. And that’s fine too. It’s whatever you want to do.”

I was at a social event a few weeks ago, and I was trying to describe your sound to the person I was talking to, and I came up with; “really good,” “agile,” and “innovative.” And then I was like, ‘well that’s every guitarist.’ So, I’ve got you here. How would you describe your playing to somebody if they just said, “Oh, you play – what do you sound like?”

“Well, melodious; quirky; phrased. There’s a lot of phrasing. A little obtuse at times. An abstract. I like to consider it emotional; it is for me. I don’t know, does that help you at your next party? (laughs)”

“Right now, I see kids doing things that they’re just fascinating. They’re amazing; their ability to navigate the (guitar) neck, a lot of it is just unique.”

I think so. I’ll spit some of those out and see if they then go and check out your music.

“Well, quirky-abstract is probably some good descriptors, I think.”

Right? I think I went to; “Well, he was that guy in David Lee Roth’s band.” And then he went, “Oh, ok then. He’s good.”

Steve Vai’s Hydra Guitar by Michael Mesker

Speaking of old nuggets, you just recently put out Flex-Able again. The 36th anniversary, I think. How did bringing Bernie Grundman in to do the mastering on it change those songs, in your opinion?

“Well, whenever you record something, your highest quality is your original way you captured it, and then, of course, you could manipulate it from there by adding all sorts of stuff. So when I recorded Flex-Able, it was all like on a quarter-inch, 8-track analog machine, and I didn’t know what I was doing really; I was learning. So I captured it the best I could, and then through the years, back then, when I released it on vinyl (because that’s all there was vinyl and cassette), that was probably the closest quality to the original.

“But then, as the digital revolution took place for the last 30 years or however long digital has been creeping up, the quality of it and the parameters of the way it captures things have changed dramatically. The converters they use, the bit rates, the sample rates, all these things change. If you suddenly have a vinyl, and then you make it into a CD back in 1983 or 1984, or whenever CDs came out.

“It was later than that, actually. Because when Flex-Able came out, there were no CDs. And then, when CDs came out, it was an interior medium for the audio experience. It had its nice points; you’re not getting crackling, the noise floor of analog vanished, but the way that it was converting the information was, it was dramatic. It was harsh; it was aggressive in a way, so you lose the noise, the noise floor, and you get clarity, but it was like it had little edges in it. So then that started to change, and as it changed, many artists decided, ok, well, now I’m going to take my record and re-master it again with this new technology. And then again, and then again.

“So with me, I’ve been doing that with Flex-Able for like 36 years. And Bernie Grundman was mastering vinyl because it’s an art. You know the way you carve the lathes that you use, how they’re set up, the way it carves the wax, the way the stampers are made, and the ears that go into the mastering process, the EQ-ing.

“And Bernie Grundman, he’s been doing it a while. He’s worked with everybody from when records started. And he’s like almost semi-retired, but since we’ve worked together for so long, he’ll come out of that to throw down some wax for me. And when I was listening to the CD of Flex-Able compared to the acetate that Bernie made of the newest version, which is the vinyl, I gotta tell you, the whole feeling of it was different. Just the way it hits your ears and your soul and your heart, just psychologically, it’s like you’re bathing in completely different waters. The notes are the same. The experience was very different.”

Are you still talking to your fellow Generation Axemen? Is there anything brewing there in the background?

“All the time. A week doesn’t go by where we’re not communicating somehow, and as a matter of fact, I just finished up my guitar camp last weekend, and Nuno (Bettencourt) was one of the guests. The thing about Generation Axe is we all really love it. And we all really enjoy getting out there; It’s almost like; you’ve worked your whole life; now it’s time to have some real fun. We’ve got great management for it, we got great techs, we got great venues, so it’s kind of like a cakewalk.

“The challenge with it is in the scheduling because everybody has a lot of things going on. Everybody has either solo work they’re doing, or they have bands like Zakk (Wylde) does his thing, and then he’s with Ozzy. And Nuno has got Extreme. And then he does his thing, and so it’s getting the schedules together, that’s the real challenge, even though we all really want to do it.”

Do you think there’s still a drive to be the hotshot virtuoso guitarist that you aspired to be when you were a teenager amongst this current climate of teenagers who are listening to a lot of programmed music and a lot of autotuned music?

“Well, the drive has never really changed, and that drive is really the competition that you set for yourself because, in reality, when you think about it, you’re only ever really competing with yourself. It may look like you’re competing with others, but the person that’s being affected the most is you. That’s undeniable. So I always, for some reason, seemed to have.

“And I think this is a trait that we all have when we find something that we love being creative with; there’s an interest there that pulls you along. It’s satisfying for a little while when you accomplish a particular visualization or something. But then there’s always that, ‘What else you got there? What else can you do here? What’s more?’ That’s fun, and we all do that. And it’s vital; it’s vital in the evolution of our creativity. We have to have that. The way that I’ve seen that in myself has changed through the years, and it’s manifested itself at times with egoic competition with the other, which later on I recognized if somebody else is doing something that is inspiring you, you can use that as inspiration as opposed to seeing it as competition.

“You’re never going to be the same after hearing any guitar player. Somehow it subtly affects you, so I embrace that.”

“So that’s a big jump, a huge jump for humanity when you make that shift because all of a sudden, the competition becomes your friend. You become friendly with it because you are learning like if I was a coach of a football team, and that’s where the word competition is appropriate as opposed to playing an instrument, I might tell them, Look, the only people you’re really competing with here is yourself, to be better than you were last time, to find more ingenious ways of moving, to be more stealthy, to be clearer each time. And every time you play a game, you’ve got more ammunition to improve yourself. If you win the game, great; if we don’t win the game, that’s fine because we’ll have an opportunity to be inspired by that thing that did win the game.

“So that’s a whole shift in human consciousness, because we’re not really there. But when you go there, you relieve yourself of a tremendous amount of suffering, because competition is a form of suffering because it’s nice when you win, but all along the way, you’re fighting; ‘If I’m going to win, I gotta get better, and be better because I have to beat them.’

“And then you get there, and you’re fighting, fighting, fighting, and then you can lose. So this is all suffering that’s unnecessary. There can be an enthusiasm in it, and for many people, there is. So for me, my mind has changed about it. I used to be a lot more; ‘how do I fit in here? Where am I going? How do I stack up? Am I delivering?’ All of these things. And it leaves you questioning yourself and not quite comfortable in your skin. That’s suffering. And as time went on, and maybe this comes with age, there can be a tendency to release that stuff, and the more that I released that, the more freedom and joy and creativity I discovered.

“So now, if I see some of these young guys, and there’s many of them now, I’ve seen several generations of the evolution of the guitar, and right now, I see kids doing things that they’re just fascinating. They’re amazing; their ability to navigate the (guitar) neck, a lot of it, is just unique. So when I see that, it would be very foolish of me to feel like I had to be better than that; I don’t even know how you do that.

“But it’s really advantageous for me to look at these young kids and go, ‘Wow! There’s elements of that that I’d like to absorb.’ And you’re going to anyway; you’re never going to be the same after hearing any guitar player. Somehow it subtly affects you, so I embrace that, and that’s a mental attitude, and that changes the quality of your whole life.”

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoTake That (w/ Olly Murs) Kick Off Four-Night Leeds Stint with Hit-Laden Spectacular [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock2 days ago

Alternative/Rock2 days agoThe V13 Fix #011 w/ Microwave, Full Of Hell, Cold Years and more

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoTour Diary: Gen & The Degenerates Party Their Way Across America

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Indie2 days ago

Indie2 days agoDeadset Premiere Music Video for Addiction-Inspired “Heavy Eyes” Single

-

Alternative/Rock2 weeks ago

Alternative/Rock2 weeks agoThree Lefts and a Right Premiere Their Guitar-Driven Single “Lovulator”