Alternative/Rock

“A Genesis in My Bed” Author Steve Hackett on Being a Musician Jumping into the World of Books

We not-so-rudely interrupted Steve Hackett’s evening writing session after a day spent putting the finishing touches on his next rock album to lob a few questions about growing up in post-war Britain, growing as a musician in Genesis and all the growing up he’s done since.

Back in December of 1970, a burgeoning and talented guitarist named Steve Hackett found himself frustrated with the bands he was playing in and with. In an attempt to nail down a new project with like-minded musicians who approached music with the same expansive and progressive bent, he placed an ad in Melody Maker magazine’s classified section that read, “inventive guitarist-writer seeks involvement with receptive musicians, determined to strive beyond existing stagnant musical forms.” Little did he know that rising prog-rock stars, Genesis were in need of a guitarist to fill the spot left vacated by Anthony Phillips and the members were scouring all available avenues (long before Al Gore invented the internet) in the search for a replacement. Little did Hackett know that those 16 words would change his life forever and start him down the path of living the dream of being a professional musician, the only dream he’d ever had.

Hackett is probably best known for his time in Genesis from 1971-77, but his story hardly stops there. Now aged 70, the London native continues to live an immensely prolific creative life with a massive discography of albums covering classical, acoustic, blues and guitar hero flash as well as the progressive rock that shined its original spotlight on him. He’s done soundtrack work, played with orchestras, studied and recorded various world music forms, was responsible for Genesis’ early lighting designs and one of the (if not the) earliest known guitarists to utilize the two-handed tapping technique.

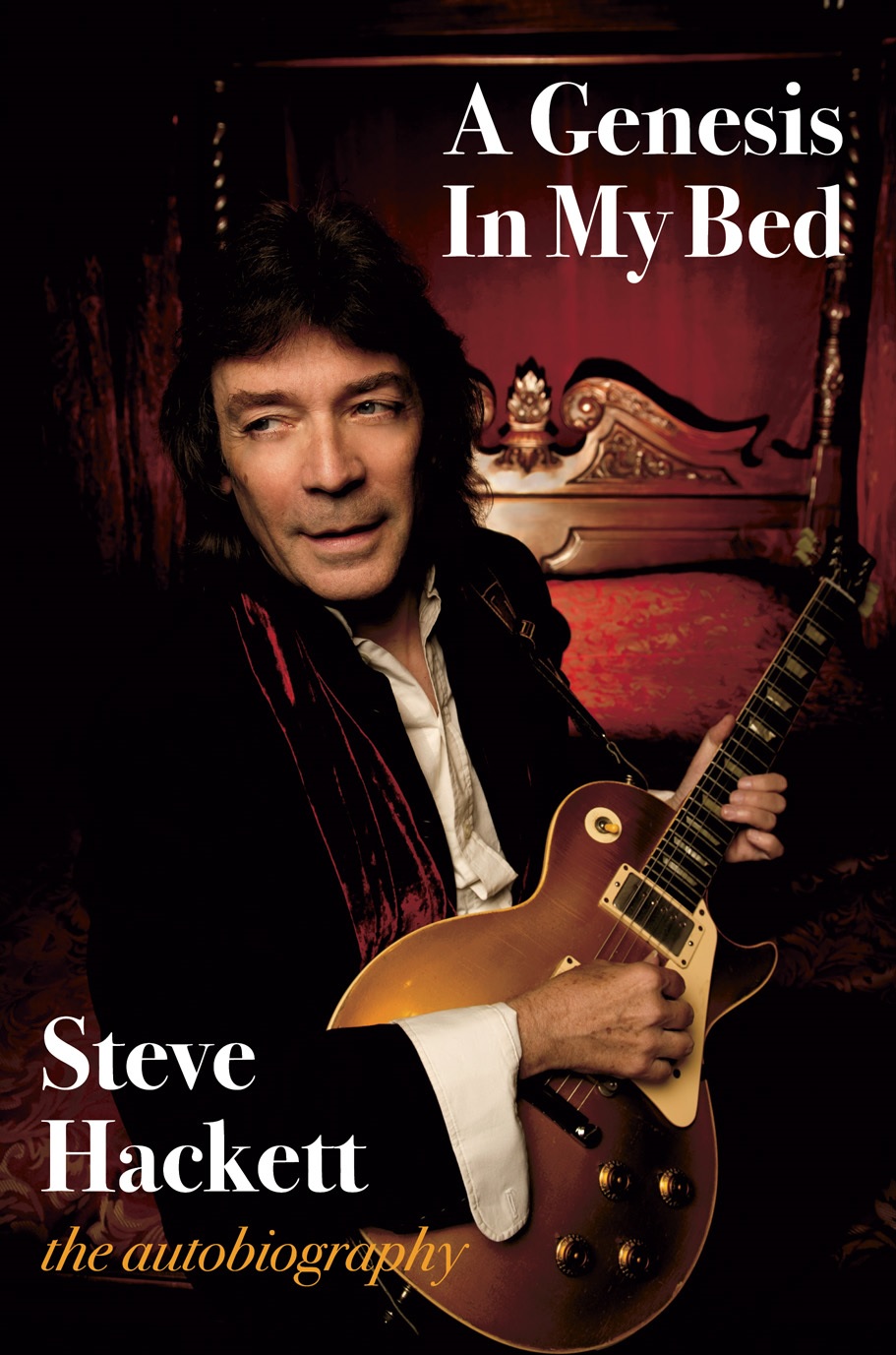

Now, the musical polymath can add author to his list of accomplishments with the release of his first book, A Genesis in My Bed, an autobiographical skim through his life, loves, adventures and obsessions (hint: all of the above are mostly helix-ed around music). We not-so-rudely interrupted an evening writing session after a day spent putting the finishing touches on his next rock album to lob a few questions about growing up in post-war Britain, growing as a musician in Genesis and all the growing up he’s done since.

This is the question I’ve been asking everyone I’ve interviewed in the past three months, like everyone, you’re sitting at home, but what are you supposed to be doing right now?

Steve Hackett: “Well, a number of things that I’m not able to do. We had to cut short an American tour when everything closed down. We were halfway through, came back and I guess I’ve been doing stuff in the virtual world. What I’ve been concentrating on is writing and recording. I had to finish off the book very quickly with finishing touches and as many anecdotes as I could conjure up. Writing the book was a major commitment.”

Were you slated to play any of the summer festivals?

“Oh yeah. I haven’t cancelled any tours, I have had tours cancelled on me, so to say. We were due to do Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and some dates with an orchestra in Germany. We had a European and British tour scheduled for the end of the year and nobody knows if that’s happening or not or until there’s a cure or vaccine or an act of God. We’re at the mercy of that and all the rest.”

So, when did you start to fancy yourself as an author?

“It was fifteen years in the making. My wife Jo said, ‘You really need to write your autobiography’ and it started a long time ago and it’s finally finished. It’s a lot of hard work, doing a book. Up to now, I’ve done the occasional blog and stuff like that, but writing a book you have to re-draw the map and chart your own course. It was far more difficult than anything else I’ve ever created. I used my wife as a sounding board most of the time about what were good ideas, what I could or should say, what I could include and will I be certified insane if I say the following. A book has to be revealing; you can’t just have the things you’re proud of or have it just be about your discography. It’s got to be about more than that. So, I’m a first-time author, no longer a virgin!”

What I noticed about your book is that it isn’t so much a heavy recollection with direct quotes and conversations regarding incidents and stories, but it’s more like your general observations. Was it difficult going back into the memory banks and coming up with a timeline about what happened when?

“For sure. My memory is notoriously bad and we were having to cross-reference dates just to get the years straight, never mind the people. I never kept a diary. Having said that, it is definitely not a work of fiction and I like to think that I haven’t trashed the people I’ve worked with. I hope I haven’t come across as too competitive. There might be a little bit of leg-pulling here and there, but I figure they can take it. They’ve written their books. I remember having a conversation with (Genesis keyboardist) Tony Banks and he said, ‘I hear you’re writing a book?’ I was like, ‘Yeah.’ Then he said, ‘Well, don’t forget I’m writing one too so be careful what you say in yours.’ (laughs)”

I read and reviewed (former Genesis roadie/manager) Richard Macphail’s book a year or two back and a similarity that struck me between his and your book was that neither of you, and many of your friends, seemed to have a life plan or a Plan B outside of music. Was that a sign of the post-war times, where the mentality was you do whatever gets put in front of you because life’s short?

“Yeah. It wasn’t like I was suddenly going to become a brain surgeon if music didn’t work out. My recollection is that I did five years of other jobs when I left school and in each of those jobs I was sometimes competent and sometimes completely useless, but I tried to keep the creative flame going and anytime I had spare time from those jobs, I would write little stories, songs or anything to keep it going creatively, somehow. I had to remember that I’m supposed to create. It was difficult and there was no other plan. I was either going to end up doing a number of boring jobs for the rest of my life or music was going to work out. I was certainly putting a lot of time in as at the end of every working day, the real work started. This went right back to when I was at school because once the school day was out of the way, the real work could start, picking up the guitar and getting on with that, picking up the harmonica, occasionally trying to write things, practicing a whole lot of the blues and a little bit of classical and it’s funny how it all worked out.

Thank God it did because as you said, there was no Plan B. My friend, the late great John Wetton (King Crimson, Uriah Heep, Asia) would tell me about women approaching him and saying, ‘Oh my son is keen to become a musician. Would you advise him to do that as a career?’ and he would say, ‘Absolutely not. I wouldn’t recommend it at all, unless you’re absolutely passionate and prepared to ride out the disappointments.’ As a reliable source of income, the music business is certainly not that. You’ll be lucky if you can make a living at it. I’ve been one of the lucky ones. I’ve come across countless people who I thought were equally talented whose careers didn’t pan out. I feel blessed to have worked with the right people at the right time.

In the 1970s the music business was sufficiently open to experimentation and album oriented rock which was a good thing. Once the emphasis went back onto singles again and pleasing MTV and A&R departments, the tail was wagging the dog and all these people who were very good at making albums were suddenly no longer hip and commercially viable and many people’s careers really went south at that point. I did sufficiently well and had three hit singles over time despite the Americans filing my stuff under ‘esoteric.’

But it isn’t the hit singles I’m most proud of, it’s the albums that have sold a fraction that are seriously challenging, but rewarding, stuff like the acoustic album I did with six pieces of Bach (2007’s Tribute). The rewards aren’t necessarily going to wing their way into my bank account. Though I hear some of those recordings being used and out on the airways and whatnot. It’s sort of like an actor doing Shakespeare. Nobody is going to get rich playing Shakespeare, but you add a footnote to the rest and join the roll call of honour for a great.”

The first chapter of A Genesis in My Bed revealed a lot about post-war hardships and socialization that I was unaware of. And the abuses many kids suffered at home dealing with fathers with undiagnosed PTSD, and brutal headmasters and teachers at school. Then, there was that whole part about how the residents of an entire street would have to share one toilet in the days before ubiquitous indoor plumbing and running water. I’m surprised that post-war Britain didn’t end up raising a nation of serial killers!

“Right, yeah, but I hope I’m not painting too Victorian a picture. I think that what I was referring to was an earlier era because I didn’t grow up with that level of deprivation. But certainly things were tough and the war literally rocked the foundations of many of the streets I grew up in. Houses were literally falling down and as a young kid I didn’t figure out why everything was falling to pieces. Where I grew up in Pimlico was near the River Thames which was heavily bombed during the war. There were sites which we weren’t allowed to play near because there was a lot of unexploded stuff and foundations weren’t safe. I think it was kind of tough growing up in an area where there were very few green playing fields. You had to really cross the river or walk some distance to get to green areas.”

Were artistic pursuits an accepted outlet or escape at the time?

“Well, my parents were very encouraging. My father played a number of instruments. He was a gifted amateur in many ways and a very bright guy. He and my mother were both encouraging and they put up with an awful lot of noise at home in a small apartment. My brother was learning flute, I was learning guitar, I’d already learned harmonica. It was a pretty noisy household. My father was painting in the living room. He didn’t have an art studio, we didn’t have a music room, I think every inch of space was being used up and being put to good use. It was quite a little factory and very productive. My brother is also a professional musician. He has a band, he sings, plays guitar and his specialty is playing flute; he’s a brilliant flute player and learned in a more formal way. He went to Cambridge to study languages, but after six months he decided he didn’t like it so he moved to Sheffield to study music and that’s what he still does for a living.”

Your book also pays great tribute and respect to the ‘60s and the musical response to what was going on in the world at the time. What do you feel is the equivalent artistic response to what’s going on today?

“Well, I write two kinds of music. I have done songs that have a more social message, ‘Behind The Smoke’ from (2017’s) The Night Siren, for instance, which is about the plight of refugees, in particular from the Middle East, and there’s a quite good video for that song. But when I look back, I think the ’60s were hugely important, the Dylan stuff, the Buffy Sainte-Marie stuff, the protest songs, the social commentary, I think we need that again. We need hope in our songs. I’m tired of hearing sassy, girl singers telling me what a drag their man is in these ‘self-empowerment’ songs. It’s very selfish, doesn’t do a lot for me and I don’t find it very inclusive. What I want is something that takes the world forward, songs with an overview. We’ve got to get out of the mess of this polarized world.

I often watch the Al Jazeera news channel and its critics say it’s ‘pro terrorist,’ but I think it’s anything but. It’s actually pretty even handed and covers contemporary issues globally whereas I find most other news stations just cover what’s going on down the road. We get a lot of American news here and it’s parochial, even though America is a great big country it doesn’t seem like a lot of them are tapped into the available information that’s out there. I hope that artists of the caliber of a young Dylan or Sainte-Marie will be born and the era of the protest song will be done again. I am addressing some of climate change, the division between rich and poor and the like on the next rock album I’m doing.”

Is your book directed at early Genesis fans or the fans you’ve gathered along the way? Is it for Genesis obsessives and historians, musicians or whomever?

“The calling card seems to be Genesis, then people realize that I do this and that as well. People might be like, ‘I remember him from Genesis. I haven’t heard anything he’s done in 50 years, but I’ll check this out.’ They might find it an interesting read and hopefully it’s not just aimed at Genesis fans who are stuck in a time warp of progressive music from 1970-75. I like to think the book goes back and examines the 1950s and takes in the fact that I’m also interested in music that is hundreds of years old and where music might go in the future.”

Your musical output has been tremendously varied. Do you find you have a particular audience or different packs of people depending on what you’re working on or putting out?

“I think different people are interested in different things. Genesis has definitely been a calling card especially since I started doing Genesis Revisited and bringing back those songs I fought very hard for years and years ago. I think that’s increased the listening base for the more recent things. When I’m playing live, I’m just as happy to bring up those old favourites as I am to break out new stuff. The new stuff is infinitely more vulnerable; anything that’s under your own name is and you have to stand there and be counted. But the band that I’ve got is so phenomenally talented that they make anything sound good.”

The Melody Maker ad is essentially the starting point for your entire musical career and has been something that you’ve banked your life’s work on. Have you ever stepped back, looked at what you wrote and thought, ‘Huh, what do you know? That certainly worked?’

“(laughs) That ad got me the gig with Genesis. It was the thing that caught Peter Gabriel’s eye and that was why he gave me a call and took a chance on me. It was very pompous, but it was making claims that the future me wanted to be able to pull off. I think it was the right thing at the right time. I was trying to come up with something that would show I was an idealist and that I was sufficiently articulate. The idea was that I wanted to be able to write songs. I called myself a writer, but at that point I was faking it to make it. It is on the day you decide to become a master chef that you become a master chef, even if you’ve never flipped an omelet. Intention is everything. I was pompous, had a lot to learn and had no sense of diplomacy. I went with all guns blazing thinking I was going to make this band strong and little did I know I was going to have to learn to write, to toe the line and learn how to socially integrate just like at school. It was a bit of a shock, but at the same time I like to think I was a shock for them and that I did covert or stealthy things that affected Genesis’ trajectory.”

Your discography is by conservative counts in the neighbourhood of 50 albums. Have you ever received a publishing check for something you don’t remember doing or completely forgot about?

“Actually, that’s right and it sometimes works out like that. My brother and I did an album together called Sketches of Satie (2000), the music of Erik Satie, French impressionist composer. It wasn’t an album we expected to set the world alight. We just happened to love the music because we grew up listening to it. Suddenly, it was being used in films and documentaries. Nothing massive, mind you. Quite a lot of my stuff has turned up in documentaries or I’ll be in a cafe somewhere and I hear my performance on such and such, particularly with the classical stuff. That does happen from time to time and there are surprises. It hasn’t been on the level of Hollywood going, ‘Tarantino needs a guitar instrumental you did way back in the days of twang,’ but music is like that. I think if you invest your music with emotion, those sorts of surprises will happen.”

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoTake That (w/ Olly Murs) Kick Off Four-Night Leeds Stint with Hit-Laden Spectacular [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock1 day ago

Alternative/Rock1 day agoThe V13 Fix #011 w/ Microwave, Full Of Hell, Cold Years and more

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoTour Diary: Gen & The Degenerates Party Their Way Across America

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Music1 week ago

Music1 week agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Indie1 day ago

Indie1 day agoDeadset Premiere Music Video for Addiction-Inspired “Heavy Eyes” Single

-

Alternative/Rock2 weeks ago

Alternative/Rock2 weeks agoThree Lefts and a Right Premiere Their Guitar-Driven Single “Lovulator”