Features

Revisiting 1959, The Year When Jazz Changed EVERYTHING

With help from the likes of Charles Mingus, Dave Brubeck, Ornette Coleman, and Miles Davis, 1959 was where Jazz started taking shape and finding its feet, and the journey from there is such a glorious adventure awash with the sound of celebration that should you ever have the opportunity, grab it with both hands and run, don’t walk.

Jazz is widely known as one of America’s original art forms, music created by American musicians with its own distinct sound, form, and intent. Evolving from ragtime and blues, the genre hit its stride in the 1920s and ‘30s with the emergence of the swing big bands and some of the most legendary of artists, namely Bix Beiderbecke, Tommy Dorsey, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Coleman Hawkins, amongst many others. With the rise of bebop in the early ‘40s, where the shift from dance-oriented jazz to introspective improvisation, extended solos, experimentation, and the shaping of the music into a true art form started to ferment, seminal artists such as Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Dizzy Gillespie emerged and were to be key figures in the future of jazz. Also included in this star line-up via Parker’s quintet was a young trumpeter named Miles Davis, an artist that would almost singlehandedly steer this music through its most formative and exciting years.

Davis, along with Art Blakey and a handful of other progressive musicians, took bebop even further in the mid-‘50s to create hard bop, which involved even more interplay, improvisation, and intense music. But it would be the rise of modal jazz and free jazz during the same time period that would break down and rebuild the structure of what people considered jazz and would allow musicians free reign to create on a higher, more spiritual level and start a fire that has continued to grow ever since.

In 1959, there was a cosmic alignment of sorts where the new band leaders had recruited the most talented of players and would release albums that would become almost a Year Zero for the genre (and music in general), from where the future of music would begin its meteoric rise. Of particular note, we would see Art Blakey and his formidable Jazz Messengers release Moanin’, John Coltrane with his Giant Steps (recorded in 1959, but only released in early 1960), and Miles Davis’ quintet with Workin’, but there are four albums that are universally renowned and that would break down barriers left and right.

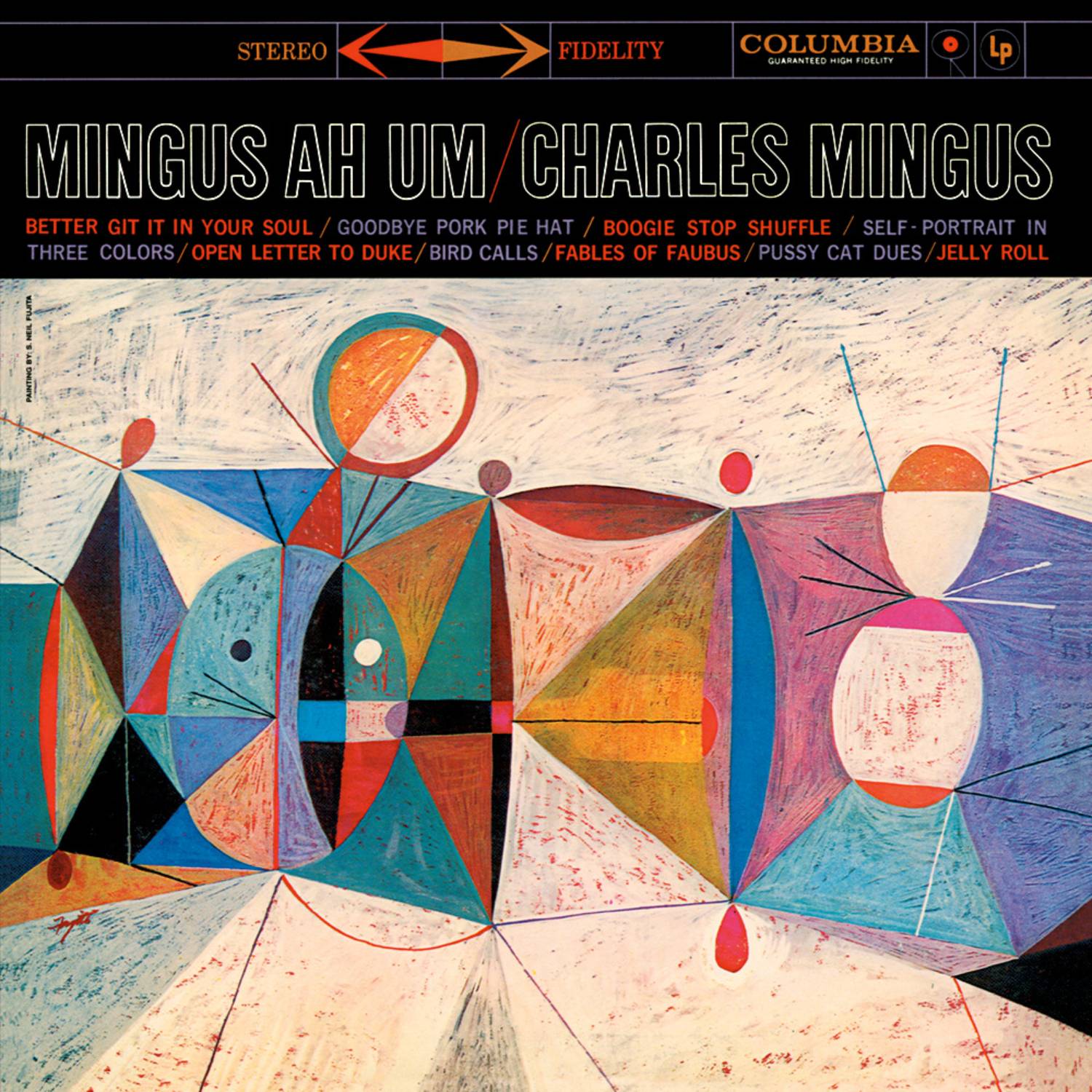

Of the four records, Charles Mingus’ Mingus Ah Um was the only one that looked back to move forward. Utilizing elements of gospel and blues and including tributes to Lester Young and Duke Ellington, it could have been a standard, albeit excellent, jazz album, but it turned out to be legendary. It’s extremely accessible, but it was the tight focus on composition and the freedom given the players that would take the music to the next level.

Mingus Ah Um by Charles Mingus was released in October 1959, via Columbia.

The first four songs would all go on to be stone-cold classics (“Better Git It In Your Soul,” “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” “Boogie Stop Shuffle,” and “Self-Portrait In Three Colors”), but the scathing attack on Arkansas governor Orval Faubus (who took a stand against integration in 1957) in “Fables Of Faubus” was powerful, provocative, and drew a line in the sand. Originally including lyrics that made no bones about Mingus’ stand but removed for the recording, they can be heard in all their glory as “Original Faubus Fables” on 1960’s Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, where he introduces it as “dedicated to the first, or second or third, all-American heel, Faubus.” Mingus Ah Um took all the bassist’s aggressions and channelled it through beautiful, funny, intricate music.

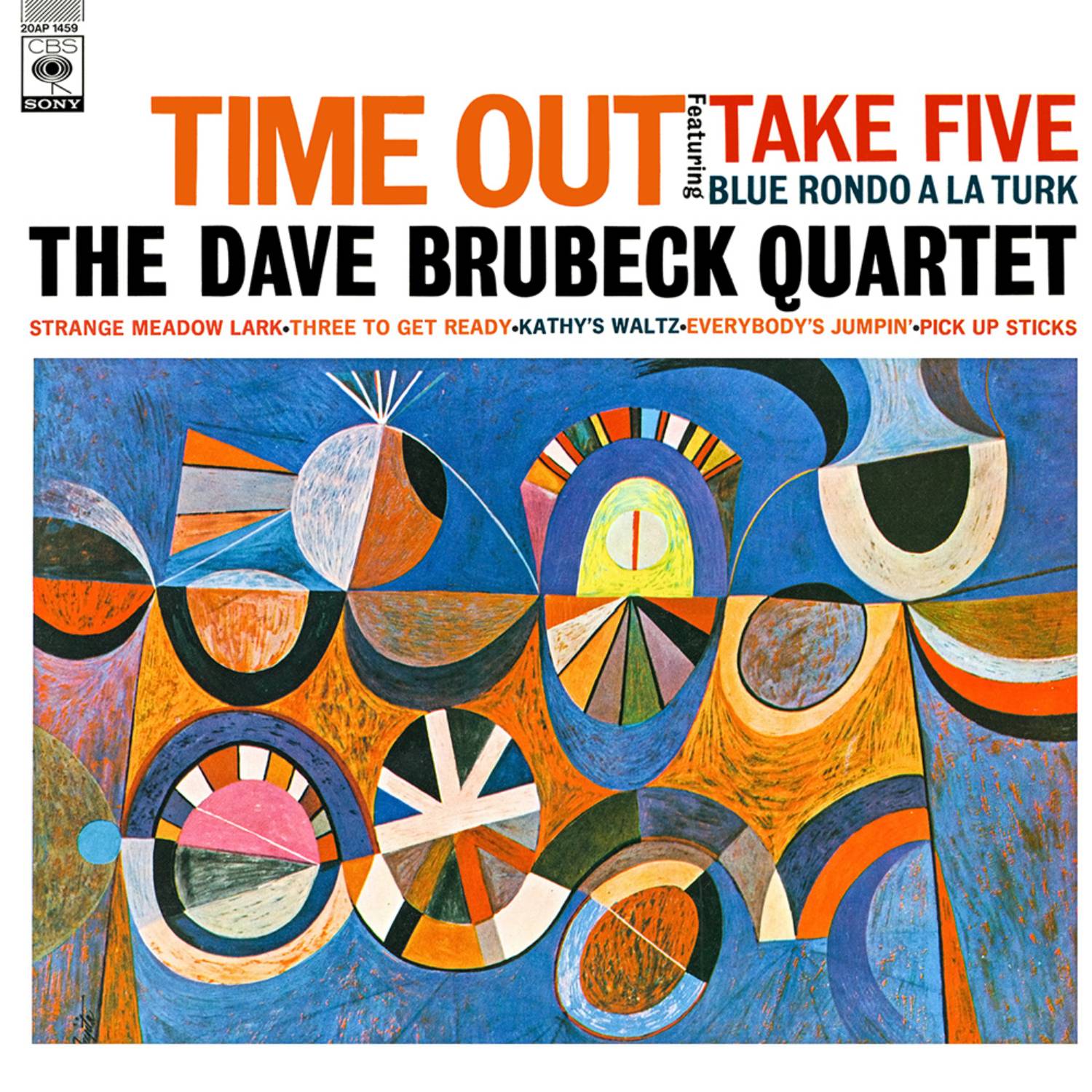

Dave Brubeck had been looking for the right band to start his true explorations and, after being amazed by Turkish street musicians playing folk music in various time signatures when he was over there as part of a tour of Eurasia, decided the direction in which he wanted to head. Once building the vastly talented quartet that included Paul Desmond on piano, Eugene Wright on bass, and percussion virtuoso Joe Morello on drums, Time Out was recorded over three sessions in 1959.

Each of the seven tracks revolve around varying time signatures to try and find a new direction, and each of them display very different feels and rhythms, many of which had not been heard in contemporary music at the time. “Blue Rondo À La Turk” was based on what he had heard in Turkey, with the rhythms playing in variations of 9/8 time and the saxophone and piano solos in straight 4/4 time, evolving into an exciting and vibrant coalescence of sound. The ‘hit’ off the album was, of course, the title track, which has gone on to be the best-selling jazz single of all time and instantly recognizable by people from all walks of life. Set in 5/4 the whole way through, it was meant as a spotlight for Joe Morello (essentially a drum solo) but with its infectious melody and playful colours, it was instantly recognizable as a song that would stand the test of time.

Brubeck was slated by his fellow jazz musicians for having a mostly-white band and selling jazz out to white America – in hindsight, he wasn’t aiming to create anything remotely commercial (the expanse of time signature explorations could have ended up as something very different) and his quartet were chosen based on their skills and musical relationships, and this album would ultimately create a hotbed of sales for all the musicians to come. So, thanks, Dave.

Time Out by the Dave Brubeck Quartet was released on December 14, 1959, via Columbia.

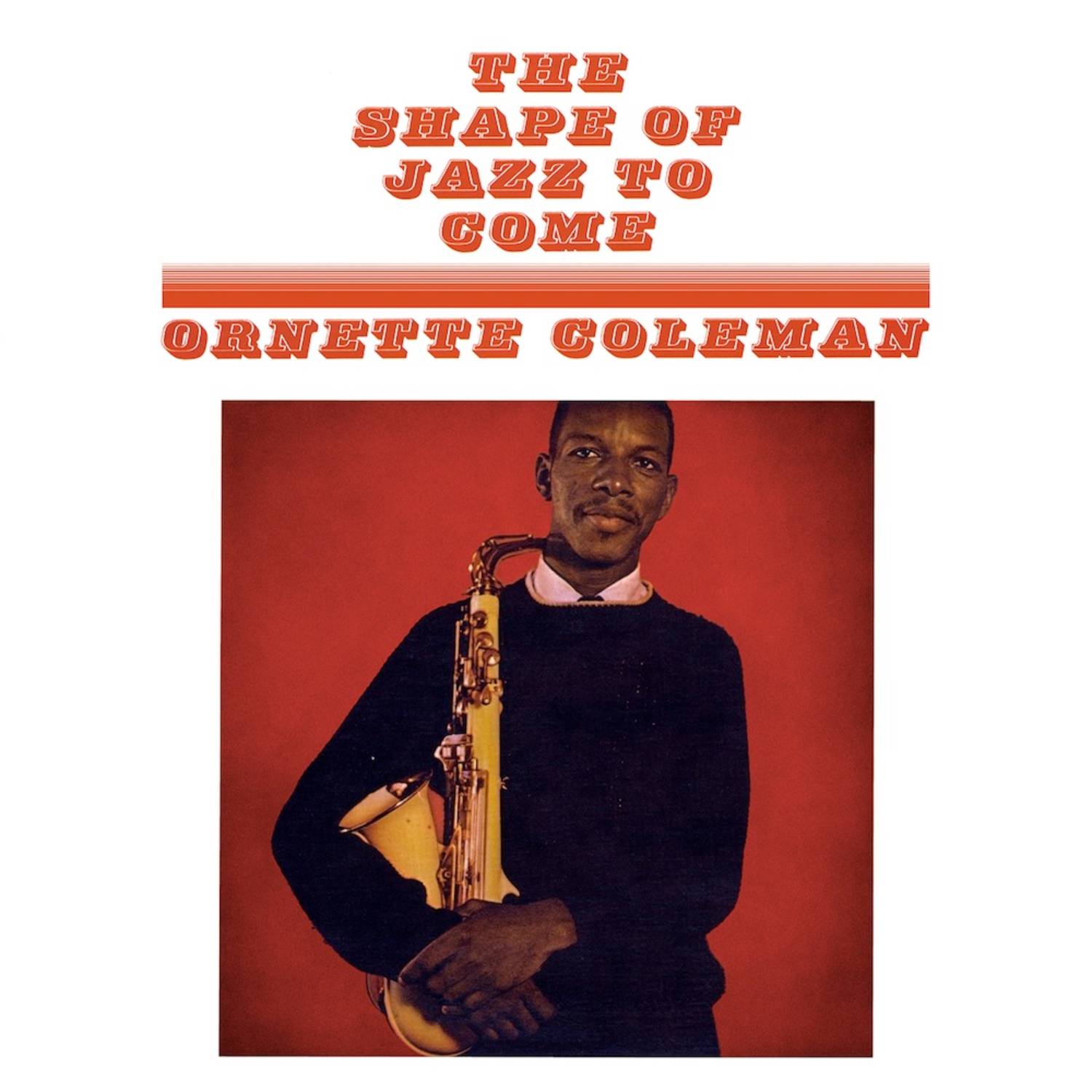

An avid student of music and its construction, Ornette Coleman had released two fairly standard albums before The Shape Of Jazz To Come, but his fevered need for exploration and improvisation led him to create what would become the holy grail of free jazz. Each of the six songs follows the theme-improv-theme structure from the bebop school, but there are no chord structures whatsoever – what this meant was that the solos taken by the alto sax, cornet, bass, and drums would be free to play whatever they wanted to in any key, at any tempo, in any rhythm, and the rest of the band would have to follow their respective lead and improvise upon improvisation. This was perfectly embodied in the opening track, “Lonely Woman,” which lures the listener in, blows their mind, and slowly eases off as if that level of genius and interplay was the simplest thing in the world.

The album was revolutionary and completely misunderstood by critics, fans, and musicians alike at the time, but within a very short time, it would become the framework for some of the most exciting music ever to be made by artists far and wide. Not too bad for a guy that got shot down for playing a white plastic saxophone (which, by the way, sounds amazing).

The Shape of Jazz to Come by Ornette Coleman was released in November 1959, via Atlantic 1317.

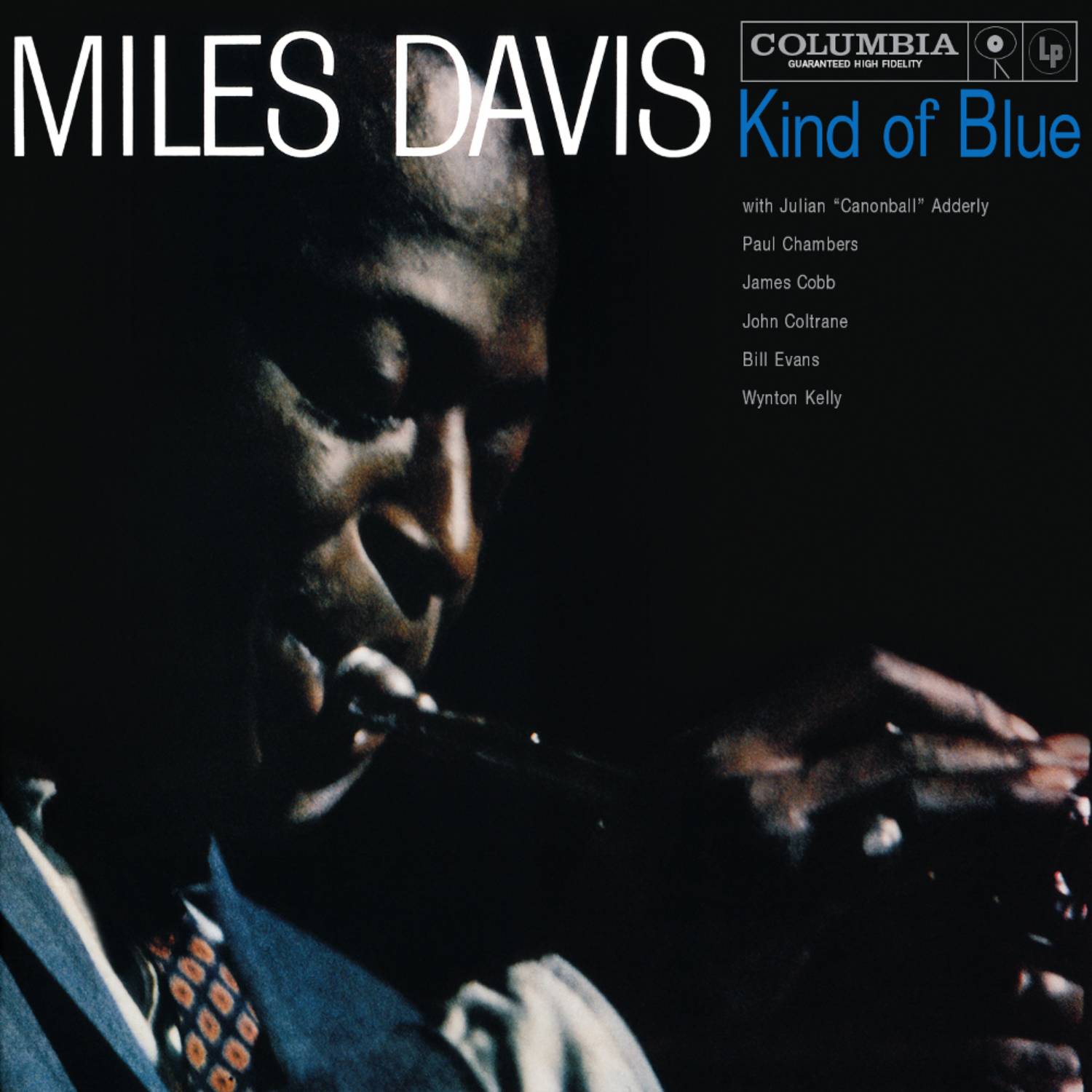

And that brings us to the Big Daddy of jazz albums, the heavyweight champion of the musical world, and the record that just keeps on giving 61 years later: Kind Of Blue by Miles Davis and his sextet of creative giants (Julian “Cannonball” Adderley on alto sax, John Coltrane on tenor sax, Bill Evans on piano, Paul Chambers on double bass, and Jimmy Cobb on drums, with Wynton Kelly on piano on “Freddie Freeloader”).

Davis had been a bebop fiend since honing his chops in Charlie Parker’s band and had already made some incredible strides in this area with some fine musicians. With 1958’s Milestones, he had started experimenting with modal jazz (which was based around the relationship between chords and scales, and the endless possibilities outside standard theory), finding bebop and hard bop overly busy and cluttered, and wanted to simplify the sound whilst still finding new ways of composing and playing. With the frankly unbelievable line-up that he took into the studio over two sessions, adding up to barely a day’s recording due to mostly first takes being the ones they used, the five songs on offer are astounding.

Kind of Blue by Miles Davis was released on August 17, 1959, via Columbia.

The overall feel is melancholy, Davis’ smooth trumpet sound packed with tone and emotion that showcases the ‘blue’ in the title, and the band (given no rehearsal and very little in the way of structure) fires on every single level possible. The experimentation and improvisation are breath-taking, but it is the way that the players lock in with each other and come up with unheard-of layers of sound that will stay with you – from the unsure intro of “So What” that sounds like a band warming up until the bass eases in with the main riff, to the freedom opened up in “Flamenco Sketches,” one feels as though they are in the studio with the band, soaking up the very real, very human sound of people creating music with other people. The record has been dissected and studied by many over the years, but it’s a collection of music that must be experienced first-hand and with an open mind, its treasures numerous and rich with vitality.

The secrets unlocked by these four albums would be utilized and stretched further in every direction by the following generations of jazz artists (and many that changed their style to fall in with this musical revolution), and it’s not a stretch to say that what was accomplished throughout 1959 in jazz would affect and inspire music from all areas in the decades to come, from rock to blues to electronica and beyond. The exploration avenues discovered also fell in with the changing America of the time, creating the perfect soundtrack for the cold war, segregation issues, human rights battles, and a country that would soon find their world ripped apart, rewired, and put back together with many scars and a new vision.

Jazz is still seen as exclusionary, untouchable music for the highly-educated that folks on the street cannot or refuse to comprehend, and this is understandable given the perception created by convoluted critics over the years. But jazz, on the most basic level, is a pure, human creation that shares our DNA and feeds the soul, both individually and collectively, a cry from the heart that is willing to embrace any that walk its path. 1959 was where it all started taking shape and finding its feet, and the journey from there is such a glorious adventure awash with the sound of celebration that should you ever have the opportunity, grab it with both hands and run, don’t walk.

-

Alternative/Rock11 hours ago

Alternative/Rock11 hours agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Hardcore/Punk1 week ago

Hardcore/Punk1 week agoHastings Beat Punks Kid Kapichi Vent Their Frustrations at Leeds Beckett University [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock6 days ago

Alternative/Rock6 days agoA Rejuvenated Dream State are ‘Still Dreaming’ as They Bounce Into Manchester YES [Photos]

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoCirque Du Soleil OVO Takes Leeds Fans on a Unique, Unforgettable Journey [Photos]

-

Music1 day ago

Music1 day agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Indie1 week ago

Indie1 week agoMichele Ducci Premieres Bouncy New Single “You Lay the Path by Walking on it”

-

Culture2 days ago

Culture2 days agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoWilliam Edward Thompson Premieres His Stripped-Down “Sleep Test” Music Video