Interviews

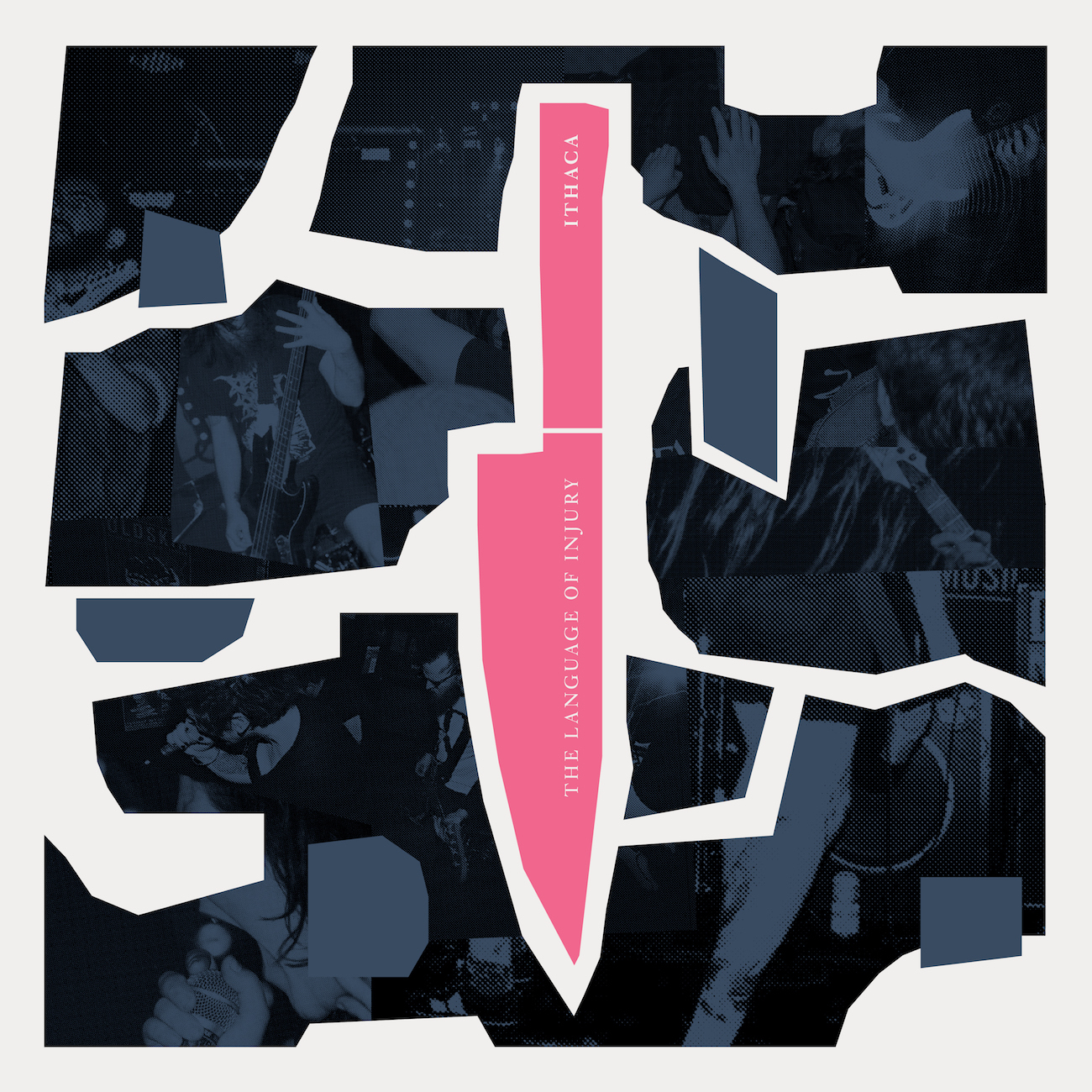

In Conversation with ITHACA: Frontwoman Djamila Azzouz Discusses Oppression, Empowerment, Female Fury and New Album ‘The Language of Injury’

In the last few years, equal representation has become a common talking point in music. One of the bands making a racket about it are London’s Ithaca, fronted by the powerhouse Djamila Azzouz, who sat down to discuss The Language of Injury (out now on Holy Roar and Deathwish) and their scene.

In the last few years, equal representation has become a common talking point in music. One of the bands making a racket about it are London, UK’s Ithaca, fronted by the powerhouse Djamila Azzouz. They’re not the only ones who bring diversity to the table; bands ranging from Svalbard to SycAmour and Venom Prison to Employed To Serve have all recently turned heads for top quality music. There has never been a better time to enact change within heavy music, but it wasn’t always like this.

“When I was growing up, I didn’t have the privilege of being exposed to musicians I could identify with. Most of the heavy bands I loved were male, and white,” Djamila reveals. There were a few exceptions, of course, and she name-checks Arch Enemy and My Ruin as reference points, “but it wasn’t enough. They weren’t artists in my scene, that I could reach out and touch.” It took her a while to work up the courage to offer her own contribution: “As a teenager, I didn’t want to risk exposing my desire to make heavy music because I didn’t know that I COULD, I didn’t know that I was allowed to. I thought people would laugh at me.” Sadly, she was proven right. “They did laugh at me. Men laughed at me over and over. But the more people I saw like me doing it, the more accepted I felt and the less I gave a shit about everyone else.”

What scene is she describing? Well, Ithaca’s origins are in chaotic mathcore, a style which they detailed well in their two blistering EPs, Narrow the Way and Trespassers. But the band had much more inside them, the capacity to push boundaries even further. The most important lesson they learned when transitioning to writing their debut album, as Djamila candidly puts it, is “just to stop giving a fuck […] We thought we knew what our sound was, but actually we were still writing within the confines of what we thought our chosen genre was and not really wanting to cross that line.” Once they realized those limitations, it was a quick shift in mindset that brought the music within The Language of Injury to light, an amalgamation of far wider influences than the band had revealed until this point. Elements of doom and black metal, indie, and post-rock all permeate the metallic hardcore formula, creating a denser palette with which Djamila paints her harrowing lyrical picture.

It’s time for us to start speaking “The Language of Injury.”

That kind of evolution can be divisive, so it’s only half-jokingly that Djamila says the most surprising reaction was that people like it. “I think one of the things that surprised me the most were people’s reactions to some of the elements we’ve chosen to include, like the vocal harmonies and clean singing, for example.” On The Language of Injury, she takes her vocals to new places, and you’d never have been able to tell that the clean-sung melodies were her first in nearly a decade “I was absolutely terrified. I wasn’t necessarily scared that people would think it sounded bad, but I half expected to be crucified by people who were used to a way more hardcore sound from us. To be honest, one of the most frequent complaints we’ve had about the album so far is that we didn’t use ENOUGH singing on it, so there you go.” In any case, the very album itself stands as an act of defiance against their own insecurities; “We’re not oppressed by the fear of what our contemporaries are doing or what they think anymore, and we wrote this album for us.”

It’s not just the music that makes Ithaca one of the most exciting bands to emerge in the last few years, though, it’s also the message. Djamila is unapologetic and ferocious as she vents her fury, and her lyrics are a highlight among highlights. While she doesn’t write conceptually, many of the lyrics on The Language of Injury have central themes regarding toxic relationships, and the damage of what is said or not said within them. “I think there was always a level of consciousness to what I was writing, but it was never explicit. It’s normally at the end of writing a record that I’m able to sit back and look at the thing as a whole and say ‘I know what this is about.’ But The Language of Injury isn’t about one particular event, it’s more a window or a snapshot of a particular time.”

It is, nevertheless, deeply personal, so was there any doubt about putting this out for the public to see? “Sometimes I feel like I give too much of myself away and I worry that people will pick it apart and analyze me, maybe even judge me for it. But then I remember that other people go through the same shit too and I’m not alone. Being hurt, being used, being manipulated. Being betrayed by those closest to you. Being taken advantage of. These are things that everyone can relate to at some point. I’m not ashamed of how I feel.”

From the album The Language of Injury, comes the frenetic and desperate energy found in “Impulse Crush.”

This lack of shame comes out in songs like “Impulse Crush,” a punishing three minutes that excoriates those who stand by and let bad things happen. “This song is definitely about questioning inaction and complacency. If people are afraid to speak up against those issues…it’s not good enough. I mean, I’m speaking directly to people who have nothing to lose here.” She turns her attention to those in the strongest position to make a difference. It’s easy for those unaccustomed to speaking out to feel overwhelmed, but it’s exactly those people who need to raise their voice. “If you’re a person of privilege and you witness bullying, sexual harassment or any form of abuse or discrimination, then you’re complicit in this. You’re part of the problem. Why are you scared? If you’re fearing for your safety, that’s one thing. If you’re afraid of ridicule from your peers, then you seriously have some work to do. For marginalized people, it’s not always that easy, it’s not always easy to interject.” She acknowledges that no one is a saint, and she has made her own mistakes about this (“and I’ve regretted it every single time”), but still urges everyone who can safely speak up and call these things out. “This is on you. Be a friend, be an ally, don’t let this shit continue.”

On both an individual and wider scale, now is a difficult time where people are learning to communicate with each other, in some cases for the first time. Often hurtful things are said during this, or necessary words go unspoken, and the significance of The Language of Injury’s title lies partially in these two sides of the coin. “One of the main things really is people saying anything at all. When you speak on behalf of marginalized folk and you’re not one yourself, you’re taking up space that isn’t yours. And then, when you minimize or doubt or contradict marginalized people’s lived experiences, you’re not only making yourself look like an idiot, but you’re making our scene unsafe for them. Just shut the fuck up.” The vitriol in her voice no doubt comes from years of experience of being talked over and being afraid to speak her mind.

The The Language of Injury album dropped on February 1st, 2019, via Holy Roar Records.

“What’s not said? I think sometimes marginalized folk are scared to speak their mind in music because drawing attention to their differences seems contradictory. I’ve fallen into that trap before; I thought that if I didn’t draw attention to me being a woman or being an Arab then no one else would bring it up either, because all that matters to me is the music. The fact is, by doing that I’m doing other people like me a disservice.” She places careful emphasis in her next words. “If you’re not ACTIVE you’re not an activist. This goes for being an ally too. Speak out too, but don’t talk OVER marginalized people!”

So what change do Ithaca advocate? “Zero tolerance. Zero tolerance for sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexual assault and abuse. Zero tolerance for shitty people doing shitty things that ruin it for everyone else.” She pre-empts the comments of coming across as being soft and sensitive, instead countering, “this is about giving everyone the same opportunities and having everyone just feel safe in it. I’m not overreacting, I just want to feel safe. I don’t think that’s too much to ask for.”

Djamila acknowledges that we’ve come quite a way, and “we’re doing much better now than we have done in the past, but it’s still not good enough. We can do better because we deserve better.” She astutely points out that heavy music has always been a safe haven for people who never felt like they belonged. “It should be a safe haven for everyone, not just privileged people.”

Before you head out, check out the full The Language of Injury album stream.

-

Music3 days ago

Music3 days agoTake That (w/ Olly Murs) Kick Off Four-Night Leeds Stint with Hit-Laden Spectacular [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock4 days ago

Alternative/Rock4 days agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Hardcore/Punk2 weeks ago

Hardcore/Punk2 weeks agoHastings Beat Punks Kid Kapichi Vent Their Frustrations at Leeds Beckett University [Photos]

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoCirque Du Soleil OVO Takes Leeds Fans on a Unique, Unforgettable Journey [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoA Rejuvenated Dream State are ‘Still Dreaming’ as They Bounce Into Manchester YES [Photos]

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoTour Diary: Gen & The Degenerates Party Their Way Across America

-

Culture6 days ago

Culture6 days agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Music5 days ago

Music5 days agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”