Features

Punk Behind the Iron Curtain: A History of Subculture Dissent in Soviet Central Europe

In Western Europe and North America, Punk Rock has been one of the most enduring cultural movements of the modern era, to this day taking countless forms and evolutions since an initial explosion of flamboyant social and political expression in the mid-1970s.

In Western Europe and North America, Punk Rock has been one of the most enduring cultural movements of the modern era, to this day taking countless forms and evolutions since an initial explosion of flamboyant social and political expression in the mid-1970s. Countless anthologies, books and articles have been written about this rich musical heritage, perhaps due to the dominance of English as an international language, with the USA and UK acting as two of the largest exporters of culture worldwide; a huge amount of music coming out of both countries over the last century.

And yet, Punk is undoubtedly an international movement, taking root in almost every country to one degree or another. One part of the world with a particularly long heritage are the countries often placed under the banner “Eastern Europe”, countries such as Poland, East Germany and Czechoslovakia that came under the grand umbrella of the Soviet Union’s “Satellite states”. In England of the 1970s and 80s, The Clash were busy paying homage to the legacy of Reggae, while Punk and Dub music began to intertwine even further in what became known as the “Punky Reggae Party”, a sound system, free-party culture rooted in the underdog spirit of dissent (see the album Bristol Reggae Explosion 1978-1983 for a fantastic compilation of underground sound-system Reggae).

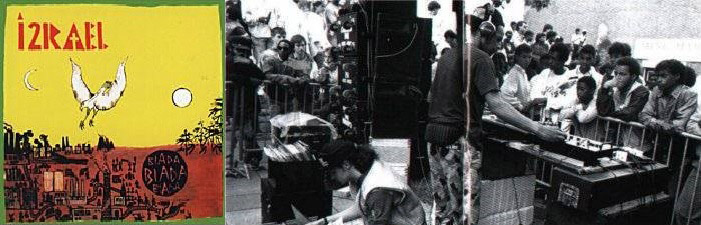

((Left) One of the earliest Polish Reggae releases by Izrael, (Right) The Wild Bunch, DJ’ing at St Pauls Carnival, Bristol, UK in 1985. Members of the Punky Reggae band went on to form Massive Attack.)

You’d be forgiven for thinking that for the countries “behind the iron curtain” much of this culture was being deliberately obscured by the Communist State machine, infamous for censoring any “anti-Communist” culture, be it music, books, films or radio. To a certain extent, this is true, with many musicians being arrested for their music. Yet there also existed a very strong sound-system culture, with a number of ‘Punky-Reggae parties’ happening in Poland and a number of Reggae bands emerging in the ’80s, leading to a very. Arguably, much of the 80s Polish Reggae presented an idealised homage to Rastafarianism, although bands such as Reggae Against Politics sought to distance themselves from Rastafarianism.

(Reggae Against Politics live at Jarocin, 1986)

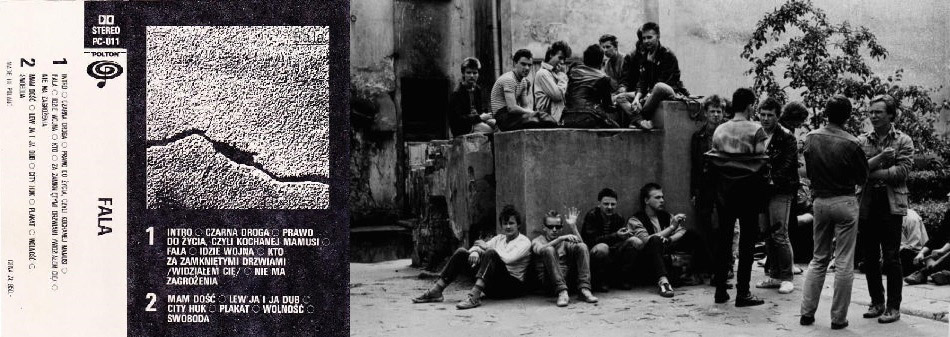

While the Dub/Punk crossover was going strong, the Post-Punk & New-Wave sound was also putting out plenty of great records in the ’80s. Long before Nine Inch Nails shot into the US mainstream with their bleak ‘Industrial’ music, you can often hear a kind of bleak, industrial sparseness to much of the Polish sound, sometimes referred to as “Zimna Fala” (translated as Coldwave). Although bands such as Siouxsie and the Banshees were playing music described as Coldwave as early as 1977 in the UK, Aneta Gatworska speculates that while ‘Eastern Bloc’ countries were not entirely cut off from global influences, much of the Post-Punk and New-Wave developed with a very distinct sound and identity exactly because of it’s relative isolation to outside influence. Just try to imagine how music developed before Globalisation and the internet.

((Left) Fala album, 1985, Polton Records. One of the earliest Polish Coldwave & Punk compilations. (Right) Image taken from ‘Beats of Freedom’ film (Images listed on Culture.pl))

She states this sound was, in many ways, a representation of the often bleak reality of everyday Polish life in the ’80s. Under Communism there had to be full employment, so many cities were still very industrial as factory jobs were propped up by the state. The communist government were also very “anti-aesthetic”, seeking to remove all traces of national heritage in architecture, often meaning that countless uniform tower blocks were built across major cities and older, historic buildings were left to decay or destroyed, leaving a fairly grim façade architecturally. That being said, it has become almost a stereotype of Poland in Western Europe to describe it as “bleak”, “grim” or “grey”, partially based on a Western media construction prior to the 1990s and our constructed Western perception of the negative ways in which Communist system affected particular countries.

(Doomy imagery on album covers from Polish ’80s Coldwave band Variete.)

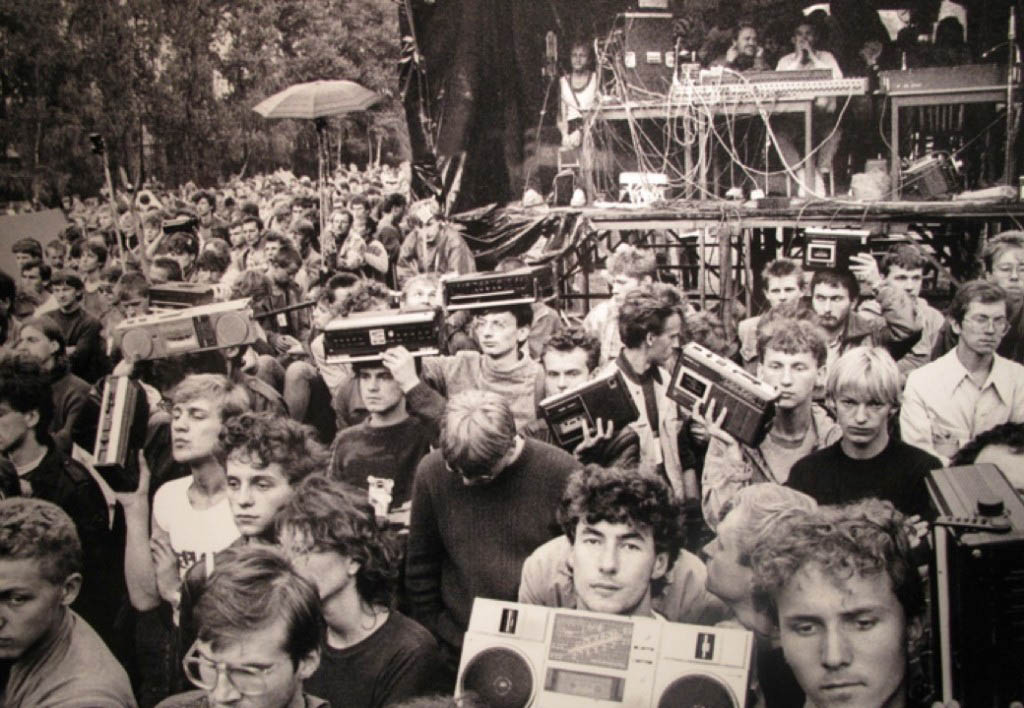

Andre Savetier writes “Between 1984 and the early 1990’s, Polish Coldwave was the mainspring of the annually organised Festiwal Muzykow Rockowych in the city of Jarocin, with a strong rebellious character in the music against the communist regime. However, the festival commercialized increasingly and, as a result of this, met its end in 1994.” For an expansive history of the festival, Grzegorz Piotrowski’s book Punk Against Communism offers a full insight into the wider political repercussions of the festival and the spirit of rebellion it tapped into alongside social movements such as Solidarnosc. Described as “The Polish Woodstock”, some claim the festival was a way for the Communist authorities to offer an outlet for angry Polish youth, to channel frustrations away from political activism and protest.

(Fans at Jarocin Festival in the ’80s, recording music not available in official Communist media outlets.)

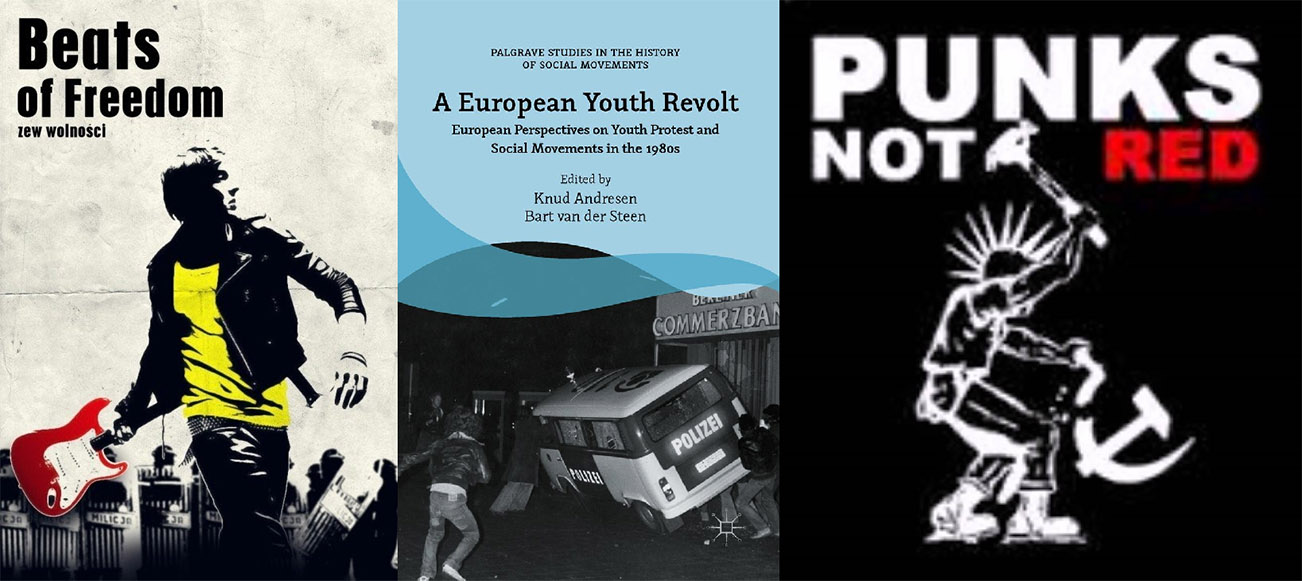

Jacek Dansky believes that many of the most vocal anti-communist Polish Punk bands went on to embrace capitalism and make a large amount of money capitalising on their status. Their objection seemed to be more against the Communist system than being against authority. In a way this is similar to aspects of the Political landscape in Poland, such as the famous activist Lech Wałęsa, who became famous for his anti-communist Solidarnosc union protests in the 1980s, then went on to become prime minister, eventually moving towards a more nationalist, ‘right-wing’ political stance. Arguably the years of Communist rule led to a boom in Nationalism in the wake of its eventual fall. Another strange tradition that emerged from this time is that shortly before the fall of Communist regime in 1989, some Punks decided to dress as Nazis as a form of antagonism, a way to protest against the greater enemy of the Communist regime. It’s debatable whether this was a genuine form protest against the Communist regime, or simply an excuse to promote Neo-Nazi ideology.

((Left) Zew Wolnosci’s documentary offers an expansive history of Polish music and political dissent. (Right) Anti-Communist imagery was used by Far-Right Nationalist Punks, both in Europe & the UK.)

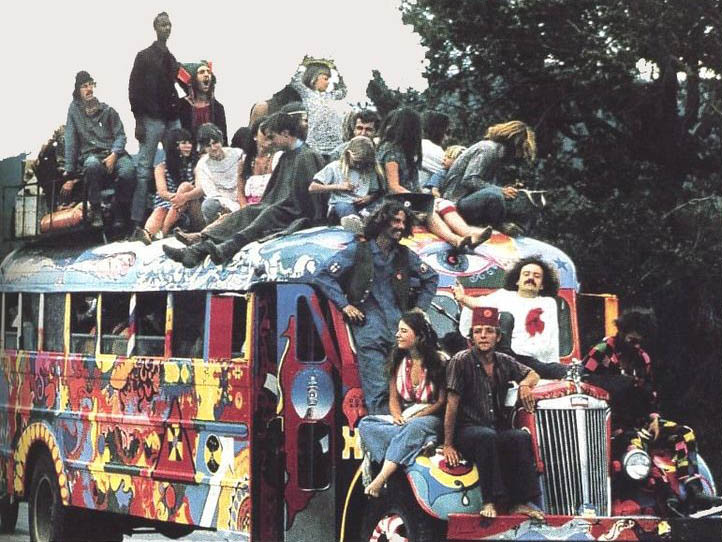

In Ukraine, however, it seems like a different story. Sasha Shvinsky states “in Poland there wasn’t so much direct government interference with culture.” The ‘Eastern Bloc’ countries were given relatively cultural autonomy, whereas Ukraine was “Soviet Ukraine”, more directly controlled by the regime. He goes on to say “In Poland they had Punky Reggae parties and Dub sound systems. It was more ‘European’ in allowing culture. I chat with older guys in the Punk scene [in Ukraine] and they say people were being imprisoned for years for being in punk bands, for being anti-communist. Lviv also had a big ‘hippy’, commune scene in the 60s, they would go around cutting people’s hair because it was also seen as anti-communist,” Sasha tells me. On the other side of the pond, however, this “long hair is Communism” sign was a genuine concern to some in the USA. It seems a ridiculous irony that some Soviet Communists viewed the cultural symbolism of men with long as “anti-communist”, while many in the USA saw it as being “Communist”.

Sasha believes that nowadays the DIY Punk scene is less established in Ukraine largely because of what he sees as a greater historical censorship. “Of course now you have access to every type of music here, but we struggle to get 100 people to a big Punk show in cities of over a million people. There is not as much desire for people to listen to this sort of music.” He tells me that he would commute 300 miles from Lviv to Kiev every weekend to play with his Grindcore band because “there were really no other people in the country I could find who wanted to play this sort of music.” This is not to say there isn’t a DIY music scene, it just seems harder to find, more disparate somehow.

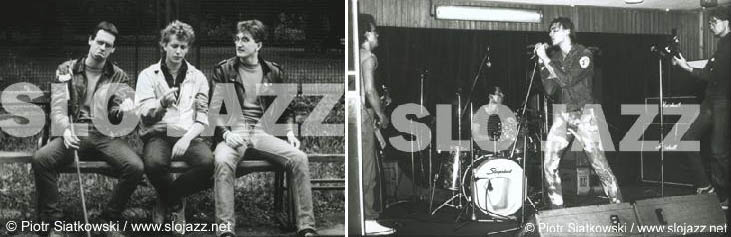

(Taken from Piotr Siatkoski’s extensive collection of Polish Punk photography over the last 30 years.)

In Slovakia, Czech Republic and Poland today you’ll find a massive following for Reggae, Punk and Hardcore artists at many major festivals that exist, yet the story for squatters and independent promoters is somewhat different. In Warsaw, a city of 3 million people, there are only 2 squats hosting independent events, compared to the massive density of alternative Punk culture in places such as Berlin. Political activists and musicians are still regularly targeted by certain nationalist groups and a highly unsympathetic police force.

It seems like the many forms of musical rebellion that emerged under communism were part of the mass discontent that already existed in various countries, feeding in to the wave of social movement. Today the musical lineage of Punk, Reggae and New Wave is rich, yet the rebellious movement is somewhat more marginalised, seen as more of a ‘fringe’ community. Although with such a rich history of dissent it seems unlikely the spirit of rebellion will go away anytime soon.

-

Alternative/Rock15 hours ago

Alternative/Rock15 hours agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Hardcore/Punk1 week ago

Hardcore/Punk1 week agoHastings Beat Punks Kid Kapichi Vent Their Frustrations at Leeds Beckett University [Photos]

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoCirque Du Soleil OVO Takes Leeds Fans on a Unique, Unforgettable Journey [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock6 days ago

Alternative/Rock6 days agoA Rejuvenated Dream State are ‘Still Dreaming’ as They Bounce Into Manchester YES [Photos]

-

Music2 days ago

Music2 days agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Culture2 days ago

Culture2 days agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Indie1 week ago

Indie1 week agoMichele Ducci Premieres Bouncy New Single “You Lay the Path by Walking on it”

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoWilliam Edward Thompson Premieres His Stripped-Down “Sleep Test” Music Video