Interviews

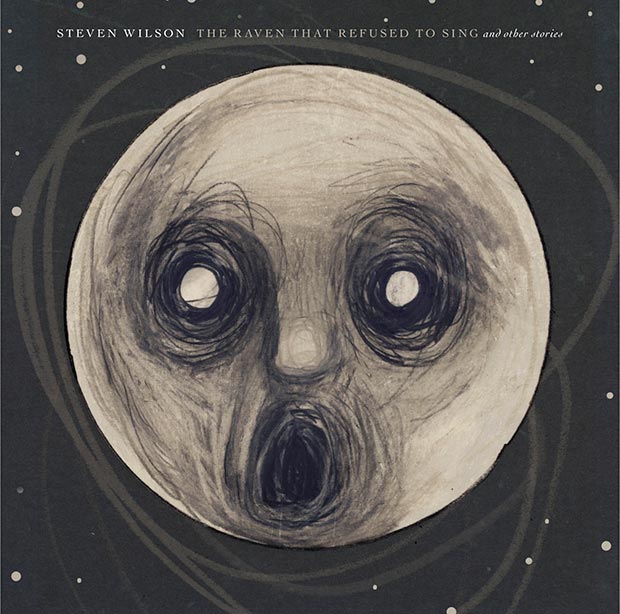

Interview with Steven Wilson; the UK Musician talks in depth about his new album ‘The Raven That Refused to Sing’

Steven Wilson (of Porcupine Tree, No Man, Blackfield and more) is currently on his second world tour for his second solo album to date, The Raven That Refused To Sing. Armed once again with an immensely talented ensemble of Guthrie Govan (guitars), Adam Holzman (keyboards), Nick Beggs (bass, Chapman Stick), Marco Minnemann (drums) and Theo Travis (flute, sax, clarinet), Steven has once more been making waves with his unique brand of music and spectacular live shows. I had the opportunity recently to discuss with Steven about themes and symbols in his music, what his music means to the younger generation, his creative process, being a musical god/sex symbol (no, really), and making people feel. And a lot more, obviously. Enjoy!

Steven Wilson (of Porcupine Tree, No Man, Blackfield and more) is currently on his second world tour for his third solo album to date, The Raven That Refused To Sing. Armed once again with an immensely talented ensemble of Guthrie Govan (guitars), Adam Holzman (keyboards), Nick Beggs (bass, Chapman Stick), Marco Minnemann (drums) and Theo Travis (flute, sax, clarinet), Steven has once more been making waves with his unique brand of music and spectacular live shows. I had the opportunity recently to discuss with Steven about themes and symbols in his music, what his music means to the younger generation, his creative process, being a musical god/sex symbol (no, really), and making people feel. And a lot more, obviously. Enjoy!

The last time we spoke, you were on your first solo tour – there was a lot of uncertainty and risk, both financially and artistically – but here you are on your second solo world tour. Congratulations on that first of all! How has it been so far?

Steven: Thank you! It’s been fantastic. I think the fact that we’ve actually now made a record as a band has given it more a sense of purpose, a sense of direction. The first tour was obviously more of putting together a band and to play the existing music. This time it’s very different because it’s the band that actually made the record together so we’re kind of more of a unit now than we were on the first tour. And it’s fantastic. I also think the first time around the audience predominantly assumed it was some little side project of mine, and after it was all over I was gonna get back to Porcupine Tree. I think people are beginning to take it a bit more seriously now and understand that this is a very important part for me and arguably the most important thing I’ve ever done. And so people are coming along now understanding that this is what I’m putting most of my creative energy into.

How have people’s receptions to this been different? I mean, now they know it’s a very epic production, they know what to expect, hopefully told others about it and brought them along. Have you noticed anything different the second time around versus the first tour?

Steven: I think people are coming along now expecting, and they weren’t expecting the first time around. I remember going out on the first tour and I said to the audience a couple nights, “Who thought they were coming along tonight and I was gonna come out with a guitar…?” And people really did think that because, y’know, it’s a solo tour. “Oh he’s gonna come out, play a few Porcupine Tree songs, a few Blackfield songs, a few songs of his own, on acoustic guitar or piano,” because that’s what a lot of guys do on a solo tour. And what they got was not that. So now I think the expectation is that they’re coming along to something spectacular, something with a strong multimedia element in terms of the film and the quadrophonic sound. But with that, there’s pressure to keep raising the bar, and I’ve tried to raise the bar again this time. And I think you have to these days because there’s so many bands out there. There’s so many bands out there on the road, probably more bands than at any other time in history of popular music.

Check out the song “The Raven That Refused To Sing”

So with this latest album, The Raven That Refused To Sing, it’s much shorter – only 6 tracks compared to Grace For Drowning; it doesn’t have a 23-minute track – what has this album meant for you and how do you see it as being similar or different to Grace For Drowning?

Steven: We kind of already touched on this – it’s mainly that I knew that I was writing for a band this time. That’s very different than writing in the abstract. The first album I was kind of writing without any specific musicians in mind and I was writing in a lot of different kind of styles. Once you have band and you have a certain idea of the personality of that band, you tend to write – or at least I do – specifically with that personality in mind and the individual personality of the members.

So this album, as you said, it’s kind of shorter, it’s probably more cohesive, it sounds more like a band – it has a “band sound” that runs through every moment of that record. And I think that in a way has made the record a little bit easier for people to digest. Grace For Drowning, critically it was very well-received but a lot of people were like, “Oh I like this track but I’m not so keen on that one.” I think for this record, it’s been easier for people to embrace the whole record because it has this kind of cohesive sound that runs through it.

So going back to the cohesiveness of the sound and writing as a band unit, I felt like this album seemed like it was so much more of a concept album than the previous one – every track was very distinctively a story; I felt like the previous one was maybe a bit more subtle. Where do these ideas come from?

Steven: Well, in this case the record was inspired by this idea of trying to parallel a record with the idea of a set of short stories. Each song is conceived as a self-contained short story but part of a collection of short stories. So the concept came from the literary world – and I’m not the first person to have done this – but I’ve always felt like music has always been something I’ve felt not just in musical terms, but also in cinematic and literary terms. One of the interesting things for me about the album – because I’m all about the album as a musical continuum, a musical journey rather than the individual songs – and one of the things about music is people think it’s kind of unusual to think that way.

But if you said to a film director, “Why do you keep making 90-minute films? Why don’t you just say everything you need to do in 3 minutes?” Or if you say to a novelist, “Why do you write a 300-page book? Why don’t you say everything you need to say in 10 minutes?” But it’s funny how a lot of the times musicians are expected to say everything they need to say in 3 minutes. And I’m not about that. I like the idea of the longer scale of things. The reason I say that is because the parallels have always been there between cinema and literature, so this time, it was very much kind of taking this idea of the classical, gothic ghost story as a basis for the music but also the whole presentation as well.

Great, this leads really well into my next question. So there’s a lot of recurring themes in this album – a lot of ghosts. Some of it’s more obvious again – “Drive Home”, “The Pin Drop” – but the title track and “Luminol”, it’s more in terms of someone that never really lived his life, and then when they’re dead, they’re not really any different…

Steven: Yes, regret and unfulfilled dreams. I think that’s one of the interesting things about the classical ghost story – it’s not about ghosts or the dead at all; it’s about the living. And it’s about the obsessions and fear of mortality, but also the ideas of regret, unfulfilled dreams, unfulfilled desires, loss. The title track is about a man who lost his sister when he was very young and has subsequently been unable to form any connection or emotional bond with any other human being. So that whole idea of loss of a human bond and sort of how it leads into regret and towards the end of his own life, contemplating his own death – these are all things to do with the living, not things to do with the dead at all. I’m not sure if I believe in ghosts – I would like to believe in something afterwards, but I’m not sure I do – but I like the idea of the ghosts as a metaphor for these things – mortality, loss and regret.

You also have other recurring symbols in your music – I think Dan had a question about that.

[Dan Samet] Yeah, just going back to your works at the start of Porcupine Tree and other things, there’s a lot of recurring motifs, mainly trains, recently ravens, and also just the recurring person of the “loner” – I think Carmen asked the last time about these people that fascinated you – but there’s always this character who’s apart from everyone else for some reason or another so I was just wondering what it was about these different things that represent or intrigue you?

Steven: That’s interesting. Sometimes people mention to me, “Oh, this recurs in your work” and I’m not even aware of it. I didn’t even realize I had a raven in my songs before.

[Dan] I don’t think it was in the songs, I think it was in the video. In “Grace For Drowning”, you had the man with the raven head who was in all the different videos.

Steven: Oh right, right – the bird – I wouldn’t have necessarily thought of that as a raven but yes. Someone mentioned to me the other day that I have used the image of a raven before – I can’t remember which song it was though. You know, the thing about the raven, in the same way that the front cover of the album is a moon – the moon is a traditional, almost cliché romantic image in any gothic fiction. The moon is a symbol of nighttime, undercover darkness, and all these things, and I think the raven is also iconic of the idea of impending death. It’s a motif that’s been used in gothic fiction going back hundreds of years. As is the ghost! The ghost itself has been used as a metaphor for something left undone, and I think these things fascinate me because they should fascinate everyone.

I think if you’re anyone that thinks about your life, what purpose your life is supposed to serve – I’m not saying it’s the same for everyone; everyone has to find their own reason – and you think about these things, then of course you do think about mortality, and you do think about regret and loss. I’m not saying you should think about trains – things that become embedded in your DNA when you’re very young never leave you. I’m sure you know that’s true, even though you’re much younger than me. Things you heard as a kid, for example, you’ll always have a soft spot for, no matter how terrible it might be to other people. And also because I grew up near a train station and I remember falling asleep always to the sound of trains coming in and out of the station – that sound to me creates an emotional reaction in me, which is part nostalgic, part romantic; it’s so many things, it’s almost impossible to explain. It’s the same with these other things you talk about that come up time and time again in my lyrics, probably for similar reasons even I’m not completely aware of.

In terms of the creative process, do you have a story which you then put to music? Is it the other way around? What works for you?

Steven:All of the above. Sometimes people ask me, “How do you write a song? Do you start with guitar or piano…?” All of the above. I don’t have any set pattern for creating music and words, or words and music. This time around, I know I wrote a couple of piece that were instrumental – I didn’t have any lyrical ideas at all – and others, I was reading a lot of short stories, gothic fiction and thought, “You know what, these might work as lyrics for these pieces of music.” So then at that point, the concept became established and so the rest of pieces were written with that in mind.

You talked before about how this is the music that you really want to do and how that’s different from Porcupine Tree, for instance, or any band where it’s more of a democratic process. So you obviously write for yourself, but do you ever have a target audience in mind when you’re writing?

Steven:No, I think it’s dangerous to think in terms of who you’re writing for when you’re writing. I’ve always believed, perhaps rather pretentiously, that the difference between an artist and an entertainer is the entertainer is very aware of their audience; the artist is incapable of considering their audience. They simply make it for themselves, because they have to, because it’s some kind of need. And I think of myself, as I said rather pretentiously perhaps, as the artist rather than the entertainer.

But it’s one thing to say that and another thing to make that your career, of course. I guess in a way I’m very fortunate in that I don’t really think about my established fanbase when I’m creating music, but whether by luck or judgment, I have a very loyal audience. They kinda seem to go with me or at least they’re curious about what I’m going to do next even if they don’t always like it. So I’ve been in a fortunate position where I’m able to make a living by actually being incredibly selfish about what I do.

Check out the song “The Birthday Party (Ghost Story)”

I think it’s really interesting as well because when you have a loyal fanbase, you can write for yourself and know that they’ll vibe with you anyway. So you can kill two birds with one stone.

Steven:Yeah, and I think if you look at the great artists – at least the ones I think are great – they were always prepared to confront the expectations of their audience, whether it’s David Bowie, Neil Young, Frank Zappa, but the point is when you have fans that are loyal, that kind of expect you to do unexpected things, they don’t give up just because you made one record that they didn’t particularly dig. They’re still curious about what you’re going to do next. So they kind of have respect for you, and stick with you.

Yeah, absolutely! So Storm Corrosion – there wasn’t a tour for it but you will be doing a show with Opeth in NYC. What’s the experience like, writing with Mikael (Åkerfeldt, Opeth singer)? I know he’s one of your best friends.

Steven:It’s easy. It’s easy. It’s just two guys that love music, who respect each other, sitting in a room, encouraging each other to come up with crazy ideas. It was easy. I can’t really articulate – it was almost like an extension of the friendship.

That’s amazing. It’s one of my dreams to have you both in the same room and to witness that chemistry, or to interview both of you at the same time. (Laughs)

Steven:The thing is, it’s like quantum physics, isn’t it. The moment you start observing, the whole thing changes. I don’t think we would have been the same if we had had somebody else in the equation, even if they were just observing. When we’re together, we feel very relaxed and secure. Mikael is one of those guys that I think I’m not afraid to suggest something other people might potentially think is a ridiculous idea. And some of the more “way out” ideas on that album are pretty ridiculous, y’know. It’s nice to be able to feel secure enough with someone to suggest these ideas that most people consider to be “way out.”

Do you think of any part of The Raven album as being an extension of Storm Corrosion in any way? I did notice you still had the Hammond organ, Rhodes pianos etc. which were present in Grace For Drowning and were a big theme of Opeth’s last album, Heritage. You also had the same directors (Jess Cope and Simon Cartwright), for Storm Corrosion’s “Drag Ropes” video as well as for “The Raven That Refused To Sing.”

Steven:Yes. Well you know what, without wishing to evade the question, I think of everything as an extension of everything else. It’s a continuum of music. It’s funny how people say to me sometimes, as if it’s a criticism, “Oh, there’s a track on your new solo album that could’ve been Porcupine Tree.” Well, of course! Porcupine Tree isn’t just me, of course, but I am still the principal writer. So of course there is going to be a sense of continuity between anything I do – Porcupine Tree, No Man, Bass Communion, the solo work. You meet people, you work with people, you have certain sounds that you like, certain production ideas you’re drawn back to. In the case of Storm Corrosion, the video was my idea – Mike’s not particularly interested in video – so I found Jess; I liked what she did with Drag Ropes and I told her, “You have to do something for my new record too.” She’s doing another one now, for the song “Drive Home”.

Check out the song “The Watchmaker”

Oh, great! We’ll be looking forward to that. Any progress on your unfulfilled dream of creating a movie soundtrack?

Steven:Not really, no. I keep telling everyone I can that this is my unfulfilled dream in the hope that somebody one day would say, “You know what, my father-in-law is Martin Scorsese!” I just figure the more people know about it, the more chance I’ve got, but no, so far no.

There’s the “pizza versus gourmet food’ analogy often used when it comes to music, popular music being the model of staleness, easily duplicated pepperoni pizza – “pop”peroni pizza, if you will. Your music is the gourmet food; you’re like a master chef, you throw everything in it.

Steven:Very nice of you to say so! (Laughs)

(Laughs) Well it’s a risk; not everyone is going to like it because it’s complicated and fancy. But I guess one of the risks of that is it tends to appeal to an older audience because they’re the ones with the money, hopefully more time to spare. What do you think of the importance of your music being more accessible to the younger generation, like us?

Steven:It’s a good question. And it’s also something I’ve wondered myself a lot. When I was young, I was into this kinda music but then I grew up with my dad who was listening to The Dark Side Of The Moon. We talked earlier about how things you experience when you’re young becoming part of your DNA. But then I remember what my friends at school were listening to at that time – it was The Jam and The Sex Pistols, the “youth music” of the day. And I liked that too. I never felt like there was ever a “them or us” thing. I just loved music, and I loved the possibilities of music. But I will acknowledge that a younger audience are predominantly looking for music which chimes more with what it’s like to be young and not so interested in weighty topics like loss and regret and fear of mortality, although a lot of metal music is obsessed with death and mortality, ironically speaking, but from a very different perspective than where I’m coming from.

I can’t change my musical personality but I do think that there is a growing sense that even the younger generation are now looking for something with a little bit more substance. You know, I wasn’t born into the age of the Internet. I’ve come to terms with it as an older person, but there’s a whole generation of kids that have been born into the era of the Internet, radio stations, American Idol, reality TV – all that bullshit. One thing that the younger generation is very good at is rebelling at whatever is the norm. If you have a generation of kids that are born into a certain scenario, they’ll find a way to rebel against it. It’s programmed in.

I think part of that is, I see a lot of kids now getting into the music that 10 years ago would’ve been considered old hippie music. Part of that is that they are looking for something. They’re turning on their TVs and looking at American Idol and The X-Factor and listening to all this fast food equivalent music, and it’s just not touching them. Then they’re hearing things like Led Zeppelin and they find something there. And then it’s like, well where’s the contemporary music that has that same buzz to it? And they find bands like me and Opeth. So the pendulum is swinging. You know, I’m never expecting to be mainstream, but there is a growing trend for younger people to be looking for something with more substance.

Yeah, hopefully! So, gender reinforces genre, and vice versa. One of the things I’ve always noticed – being a metalhead before getting into more progressive stuff – is that one of the hallmarks for these genres is the gender stereotypes. The women sing beautifully, delicately, expressing femininity, singing about relationships and love; the men are always using screaming, more aggressive, distorted vocals. You seem to be outside a lot of these stereotypes – you’re very graceful, you don’t use distorted vocals. Yet in your music there’s a lot of male characters present. What role (if any) does gender and sexuality play in your music?

Steven:It’s interesting that you asked that question, because I was talking to someone about how the stereotypical progressive lyrical content tends to be more fantastical, and I think that is quite a turnoff for women. Because mine isn’t – I mean, I do write about relationships and love and loss and regret – I think I do have a large female element to the music. I’ve always said it’s very interesting when I do interviews, I always notice the guys ask me about the people in my band, what it was like working with Alan Parsons, all this stuff, and the women that interview me would always ask about lyrics. The guys never ask me about lyrics! It is a difference between the two genders. Women are more interested in the emotions that went into creating the music and the guys are more interested in the trivia – which studio did you record in, what string gauge did you use. And I’m interested in both. But then I grew up being very much a product of my father and mother’s musical taste, and my mother was listening to disco music and my father was listening to the more intellectual rock music.

It also extends to the way I think about music, because I have these extraordinary musicians in my band that are capable of doing amazing things, and usually I’m telling them to play less, play simpler. Guthrie (Govan), the guitarist in my band – a lot of people say he’s the best guitarist on the planet right now; he’s extraordinary. I say to him, “I want you to break my heart with one note. I don’t wanna hear like 3000 notes; I want you to just get me there with one note.” And he completely understands too. This is a roundabout way of answering your question, but I think that that’s the difference between women and men – women are more attracted to the heart and men are more attracted to the intellect. That’s a simplification of course – there’s a grey area between the two – but I think if I do have stronger women’s demographic, it’s because I do write more from that perspective sometimes.

Check out the song “Luminol”

A lot of your fans view you as a god or a sex symbol. What is your reaction and do you have any thoughts on that?

Steven: Really? A sex symbol?! I’ve never heard that before! [Laughs] Listen, words like “god” and “genius” are overused a lot, aren’t they? To me, when people say that I’m a musical god or musical genius, basically what they’re saying is that the music has touched them, very deeply. That’s amazing. And plenty of people that say the complete opposite as well – that I’m an asshole. These days you only have to spend a few seconds on the Internet to find someone that hates you and someone that loves you, and in a way that’s good because it really keeps things in perspective and balance for you.

But I think I’ve been very persistent in my career. And when you get to a certain point – I’ve been doing this for 20 years now – where you’re still bashing your head against the brick wall, and you still haven’t sold out or haven’t compromised your musical ideals, you get a certain amount of respect almost just for doing that. And there aren’t too many people who do that. I look around me and there aren’t too many people that started when I started – Mikael (Åkerfeldt) would one of the few others I can think of, he’s been doing it for 15 years and never been interested in compromising – there’s not a lot of people like that.

It takes a lot of patience, and endurance.

Steven: It takes a lot of patience and a lot of stupidity. [Laughs] From Mikael’s perspective too, he couldn’t compromise even if he wanted to. It’s just not in our DNA to be able to do that. I feel physically sick at the idea of doing something for the wrong reasons. Very early on in my career, I had to write music for commercials and things, just to keep myself going, and it really did make me feel ill.

Well, I guess it’s kinda nice that people find that attractive? [Laughs]

Steven:Well I’ve never heard the sex symbol bit before! [Laughs]

So we found Uncyclopedia, a parody website of Wikipedia, and it said things like, “Steven Wilson – Does everything and is everything. Has the ability to play five hundred symphonies with one pair of limbs, also controls the bands” and there’s pictures of you with captions like “Just look at him!!! Who wouldn’t follow this stunning god off a cliff?” We thought it was hilarious.

Steven: Wow! Is this written by a girl or a boy? It’s pretty funny. I think the perception is that I work a lot and that I do a lot of different things, and I do, you know? But I have these incredible people around me that make it look better than it would otherwise – incredible musicians. But I think the main thing I aim to be is the director. I’m not a great musician. I’m not a great singer. But I think one thing I’m good at is in a way having a vision and finding all the pieces to put it together, to make it real. To be a band leader, to be a musical director – that’s what I’m good at.

You’re one of the few musicians that can be very technical, very experimental, without losing the musicality aspect of it. Do you have any advice for aspiring writers and musicians, especially from our generation?

Steven: Listen. Listen. It seems really obvious, but when I was young I had a voracious curiosity for all sorts of music. The problem I have with a lot of modern music is, they give me a demo, I listen to it and I can tell exactly what their record collection is within 30 seconds. People give me CDs and say “It’s progressive metal in the style of Opeth or Porcupine Tree” and I get that sinking feeling straight away that I just know what it’s going to sound like – nothing fresh. What people often underestimate about people like me and Mikael is, well we listen to a lot of music that inspires us but we also listen to music that’s way outside what you might obviously hear on the surface of our own music. And I believe that’s one of the reasons it’s special. It’s because there are influences coming in from avant-garde classical music, Abba, jazz, folk, soundtracks to horror movies – anything you can think of. It’s all going into the melting pot.

The problem with a lot of young musicians is they find themselves immersed in just one musical style, death metal for instance. The world doesn’t need more death metal bands, it really doesn’t. But it doesn’t stop there being another hundred death metal bands being formed every week. I think it’s nice now when you listen to something and you can’t quite pinpoint where it’s coming from. It happens rarely. I think when it does happen, it’s because the people who made it listen to music way across genre and created some new hybrid, mixing their influences together and coming up with something unique.

It’s a facetious thing to say, but young musicians should listen, and something you already mentioned yourself – don’t get tied up in the musicianship. Because it’s not about playing a hundred notes. It’s about playing one note and making people feel something.

-

Music4 days ago

Music4 days agoTake That (w/ Olly Murs) Kick Off Four-Night Leeds Stint with Hit-Laden Spectacular [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock6 days ago

Alternative/Rock6 days agoThe V13 Fix #010 w/ High on Fire, NOFX, My Dying Bride and more

-

Hardcore/Punk2 weeks ago

Hardcore/Punk2 weeks agoHastings Beat Punks Kid Kapichi Vent Their Frustrations at Leeds Beckett University [Photos]

-

Alternative/Rock2 weeks ago

Alternative/Rock2 weeks agoA Rejuvenated Dream State are ‘Still Dreaming’ as They Bounce Into Manchester YES [Photos]

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoTour Diary: Gen & The Degenerates Party Their Way Across America

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoDan Carter & George Miller Chat Foodinati Live, Heavy Metal Charities and Pre-Gig Meals

-

Music7 days ago

Music7 days agoReclusive Producer Stumbleine Premieres Beat-Driven New Single “Cinderhaze”

-

Alternative/Rock1 week ago

Alternative/Rock1 week agoThree Lefts and a Right Premiere Their Guitar-Driven Single “Lovulator”